FOCUS VI | Texts on Mail Art: 1970-1985

Sorry Ray, Mail Art does have a history!

By Vittore Baroni

When, almost forty years ago, I discovered the existence of Mail Art and I begun to put the concept of free and direct postal communication into practice, I was possessed by a great curiosity to find out how, where and when this vast international phenomenon of exchange and cooperation had originated (the “why” question was easier to answer: so much instructive fun!). I therefore started straight away my investigations through the mail, as Google was still decades away. To begin with, I subscribed to a few Mail Art related magazines such as Anna Banana and Bill Gaglione’s “Vile”, Judith Hoffberg’s “Umbrella”, Aart van Barnevald’s “Rubber”, Ulises Carrión’s “Ephemera” and Charlton Burch’s “Lightworks”. I then proceeded to collect - with a little help from Michael Scott, John Held Jr. and other more experienced networkers - photocopies of the most relevant articles on postal art that had appeared in the early 70’s in such diverse publications as “Rolling Stone” and “Art in America”. I also became an avid reader of the few books on the subject that sporadically appeared in print, mostly in the English language, starting with the seminal anthology Correspondence Art edited by Michael Crane and Mary Stofflet (Contemporary Arts Press, San Francisco, 1984) and Maurizio Scudiero’s book Futurismi Postali (Longo Editore, Rovereto, 1986) about the pioneering postal work of the Italian Futurists. For the very same reasons that compelled me to become a music journalist - to get to know personally the musicians and learn more about the music that I loved - I also tried to contact directly (by phone, if necessary) and if possible to visit the postal authors that intrigued me most, such as the already legendary Guglielmo Achille Cavellini (but I also appeared on the doorsteps of Romano Peli, Rod Summers, Guy Bleus, Paul Carter, Ron Crowcroft and many others). I thought that it was important, as a newcomer to the medium, to learn as much as I could about Mail Art, if only just to avoid to repeat postal concepts and actions already done by others (as George Santayana’s famous quote states, “those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it”).

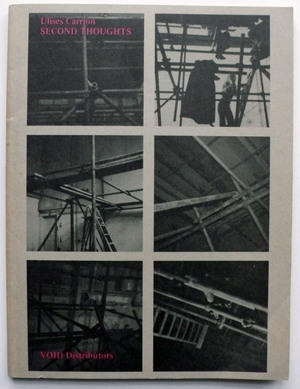

Original texts (artists’ statements, rants, manifestoes, letters, articles, essays, anthologies, etc.) are definitely of paramount importance to arrive at a full understanding of the vast constellation of often subterranean efforts from obscure and underestimated authors that constitute the Mail Art network. The exchange of works and creative experiences by mail was not just a novelty concept or a great idea to be exploited for personal amusement, it was as I learned from Ulises Carrión (see Second Thoughts, Void Distributors, Amsterdam, 1980) “part of the guerilla war against the Big Monster”. It was the total sum of hundreds, maybe thousands of personal untold stories out of a vast, varied and loose association of individuals who rebelled against the monopoly of the Big Media and favored alternative and more interactive systems of communication. A proto-“social network” with a genuine revolutionary attitude (and no side banners with ads). It is also true that history has always been written by the winners. I soon realized, flipping through mainstream art books and magazines, that Mail Art has always been largely ignored by art critics and historians. Since the phenomenon was based on free exchange and involved professional artists and non-artists alike, it was of very little interest to critics, galleries and museums (often, they simply did not “get it”). But if the existence of Mail Art has passed understandably unnoticed outside the boundaries of the postal circuit, on the other hand the history and theory of postal art has been thoroughly documented and debated inside the network itself, thanks in particular to the many practicing mail artists who possessed skills (and jobs) as writers, journalists or academic researchers. The community of international networkers has thus produced an incredible amount of writings, scattered in numberless magazines, pamphlets, catalogs and books, mostly self-published and distributed by mail in limited editions, and also in personal communications housed in hundreds of small private archives around the world. Through donations and acquisitions, in time a great quantity of these publications has ended up also in public libraries and in the archives of important museums (such as the MoMA in New York or the MART in Rovereto, Italy), available therefore to students and scholars as well as to the general public. Yet, the number of significant essays on Mail Art not written by active mail artists (e.g. Networked Art by Craig J. Saper, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 2001) can still be counted on the fingers of one hand. Mail Art remains until today probably the largest relatively “unknown” phenomenon in the history of art. Just open any art textbook at the index and verify it by yourself.

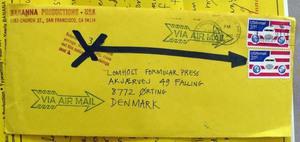

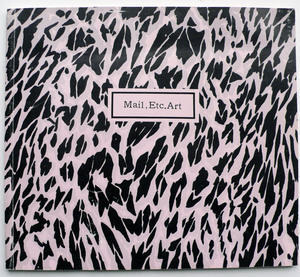

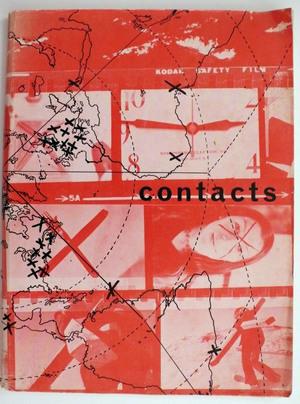

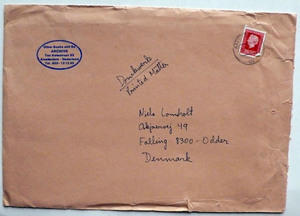

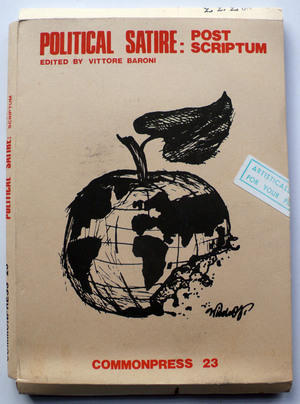

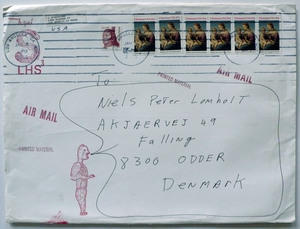

Mail Art Archives are a bit like Ali Baba’s cave, each of them contains a different collection of amazing treasures that tell the story of the postal circuits from a slightly different point of observation. However, certain texts and publications remain as milestones, unavoidable points of intersection in the expansion and evolution of the Eternal Network. For example, many books and magazines housed also in the Lomholt Archive have proved extremely useful in my formative years as a networker, such as the assortment of printed materials related to Monty Cantsin and Neoism (with further insights into this anti-movement provided by the many personal letters by David Zack, Istvan Kantor, Al Ackerman, Peter Below, Pete Horobin, etc.), the elucidations on single postal projects such as Plinio Mesciulam’s Discourse on Mohammed (Edizioni Rinaldo Rotta, Genova, 1979) or well known magazines like “Commonpress” (a true collaborative concept, with each issue edited by a different networker, I did n. 23), “CabVolt”, “Vile”, “Doc(k)s”, “Geiger”, “Umbrella”, “Spiegelman’s Mailart Rag”, “Cisoria Arte” and many others. The inventive diaries and the catalogs of postal projects created by authors like Guglielmo Achille Cavellini and Robin Crozier can be considered true “artist’s books”, but also contain a wealth of data and useful information, just like the best Mail Art catalogs, with enlightening prefatory essays, interviews and manifestoes (for example, Mail, Etc. Art organized in USA in 1980 by Bonnie Donohue and Ed Koslow included a lengthy conversation with Ray Johnson). Even given the planetary dimensions and the eclecticism of the phenomenon, we can identify then an essential backbone of texts and publications that form the basis of the consensus of what we generally call Mail Art. But when you explore any Mail Art archive, looking in the niches and crannies of the magical cave made of cardboard boxes, you always end up discovering unfamiliar publications that may fill holes in your comprehension of postal art (e.g. the Contacts catalogue by Bill Vazan from the early 70’s, that I saw for the first time in the Lomholt Archive). The whole Mail Art tale may not yet be common knowledge, but its secrets are well-preserved. Open sesame!

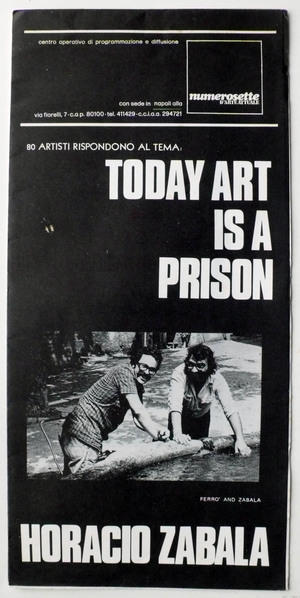

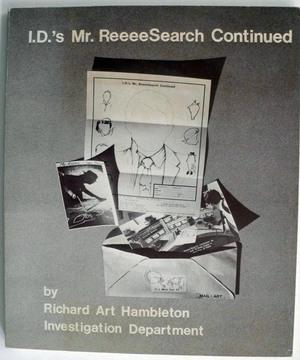

So, will Mail Art continue to be studied and commented mostly by mail artists, as a big snake gnawing its tail (see for example Graciela Gutiérrez Marx’s Artecorreo: Artistas Invisibles en la Red Postal, Lunaverde ediciones, Buenos Aires, 2010)? Another paradox enters into this equation, since many networkers seem to instinctively reject the idea of "historicization" of correspondence art (as the author of many texts on the subject, I have often been the target of slightly hostile manifestations), on the ideological basis that this would mine the open, horizontal and anti-hierarchical nature of the medium. A true history of Mail Art should not just single out a limited number of authors as representative of the phenomenon, but really motivate and explicate its inclusiveness and openness, the short-circuit of high and popular culture, the overcoming of the separation between artist and audience, the emergence of “networking” as a new cultural strategy. The aversion toward historicization may have been fueled also by a widely circulated quote by Ray Johnson, the founding father of art by post: "Mail Art has no history, only a present" (a verbal pun on "present" interpreted as "gift"). Sure, in the postal process the practice of giving is more important than the cult of authorship, and Johnson certainly gave his estimators a hard time refusing to conform to the rules of the art system, but this does not mean that the pure and simple facts can’t be reported remaining faithful to the true, open and collectivistic nature of Mail Art, yet giving the due importance to each original personality active in the network. After all, Johnson is finally obtaining today the kind of critical attention that he surely had deserved during his lifetime, and the recent appearance in print of collections of his mailings (see Not Nothing, Siglio, Los Angeles, 2014, or the 2014 reissue of Ray’s 60’s classic The Paper Snake) leave us astounded for the scope, complexity and wit of his postal manoeuvres. Yet, the strength of Mail Art lies in its diversity, as countless projects have proved (just think of all those collections of “forms” which provide a wide array of answers to the same question, from Horacio Zabala’s Today art is a prison to Richard Art Hambleton’s I.D.’s Mr. ReeeeSearch and the various surveys of the Lomholt Formular Press), so we should hope that Johnson is only the spearhead that anticipates the emergence of more unpublished gems and historical reprints by different postal authors. Ray’s contribution to the postal art medium is fundamental, but there are dozens, hundreds of other fascinating Mail Art characters waiting to be rediscovered in detail, as can be sensed flipping through the names included in amazing home-made publications such as Henryk Gajewski’s Mail Art Hand-Book (Amsterdam, 1983) or reading the extensive collection of “Mail Interviews” gathered together in pamphlet form by Ruud Janssen in the 90’s.

Today the Web gives you instant access to a large number of writings on any subject you may think of, but unfortunately a great part of the most significant Mail Art texts, particularly those written in the early years of the medium (see for reference the massive repertory Mail Art: An Annotated Bibliography by John Held Jr. for The Scarecrow Press, Metuchen/London, 1991) are still not available online. Public and private archives, therefore, maintain a essential role in the preservation of Mail Art’s rich pre-Internet tradition. The world of media has changed dramatically in the past two decades, offering new powerful tools for creative interaction that have in large part replaced the old letter-and-postage-stamp methods. Mail Art slips more and more into the past, while the generation of mail artists who started their postal activities in the 60’s and 70’s slowly disappear one by one. The process of ageing finally comes full circle with the appearance, in recent years, of books and web sites (such as the Lomholt Mail Art Archive, Ginny Lloyd’s Gina Lotta Post Artistamp Museum and Archive or Greg Byrd’s freshly started Toast Postes Artistamp Archive) that try to document the involvement with the postal medium of single authors throughout their entire careers. Mail artists grow old and feel the need to reconsider their extraordinary journey, to put in some kind of order the wealth of materials they have produced and collected. The initial results of this “senile” phase in the long history of postal art, with the publication of mammoth volumes dedicated to the Lomholt Mail Art Archive (2010), Carl T. Chew’s Triangle Post (2012), the Artpool Archive in Budapest (2013), or less huge but still historically relevant publications as those related to the Morris/Trasov Archive (1992), Johan Van Geluwe’s Museum of Museums Archive (1999) and Klaus Staeck’s Archive (2013) are probably just the proverbial tip of the iceberg. Willy-nilly the reluctant networkers, maybe the day is not so far anymore when also Mail Art, the Cinderella of the contemporary avant-gardes, will be given its due in art textbooks. Whatever Ray may have said.