FOCUS II | Polish Files in the Lomholt Mail Art Archive

By Grzegorz Dziamski

Kostołowski and Net

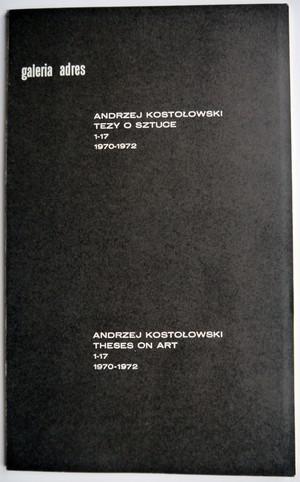

Niels Lomholt established a contact with Polish artists in 1972. In that year he received two mails from Poland. Both from Łódź, from Adres Gallery founded and run by Ewa Partum. The first one was a thin, Polish-English book by Andrzej Kostołowski "Theses on Art 1 - 17", the other one was a catalogue of work performed by three artists – Włodzimierz Borowski, Jan Świdziński and Krzysztof Wodiczka.

The author of theses on art, Andrzej Kostołowski, was a respected critic of the middle-aged generation who has supported the modern art in Poland. In the early 70s, he was fascinated with the conceptual art and published several articles on it. In the 1970, he began to write down his thoughts about art in the form of theses - theses for discussion. In this way he overstepped the thin line separating art from art criticism and coming at the same time closer to the extreme version of the conceptual art, as it was understood at that time in Poland, to art as reflection on art. In one of his theses, thesis XI, Kostołowski wonders whether it is possible to practice art of the art theory. He wonders whether what he deals with, engaging so much enthusiasm, can be considered art? Over the next few years Kostołowski added subsequent theses on art, ending up with 33 of them.

In 1971, Kostołowski together with Jarosław Kozłowski published the "Net" Manifesto. The manifesto laid down the principles of artists’ cooperation. The Net, as the authors of the manifesto wrote is “a) extra-institutional, b) it consists of private homes, artists’ studios and other places where art proposals emerge, c) the proposals are intended for those interested, d) they are accompanied by publications of any form (manuscripts, typescripts, prints, tapes, films, slides, photographs, leaflets, etc), e) Net has no central point and is not coordinated, f) Net points are in various towns and countries, g) the points are in contact with one another through exchange of correspondence, projects, notations and other forms of articulation, which exchange enables parallel presentation of these at all points at a time, h) the idea of the Net is not novelty, when Net comes into being, the idea no longer has its author, i) Net may be used and duplicated at will.” “Net” manifesto was sent to 300 recipients from all over the world as an invitation to participate in the new network.

The Net Manifesto laid foundations for the way of functioning of all independent galleries in Poland in 1970s; all of them, including Adres gallery and Akumulatory 2 gallery, established in Poznań by Jarosław Kozłowski on the Net basis, wanted to function as active points of the international Net.

The work of the three artists, Borowski, Świdziński, Wodiczko is a record of their common action performed in Łódź in April 1972. It is one of the most interesting works of the Polish conceptual art, in the style of Dan Graham, but rarely reminded of - not even shown at the exhibition "Conceptual Reflection in the Polish Art (Warsaw, 2000) or at the "Conceptualism. Photographic medium” (Łódź 2010). The work is untitled - it is a kind of an exercise, as it comes from the period when many artists, not only in Poland, believed that there would be no artworks in the conceptual art. The artists formed an equilateral triangle, each represented one of the vertices of the triangle and then took pictures: Borowski took a photo of Wodiczko, Wodiczko of Świdziński and Świdziński of Borowski. Then they formed a slightly larger equilateral triangle and again took photos of themselves. They repeated this seven times, all the time increasing the distance between the vertices of the triangle until the photographed figures disappeared from the view of the cameras.

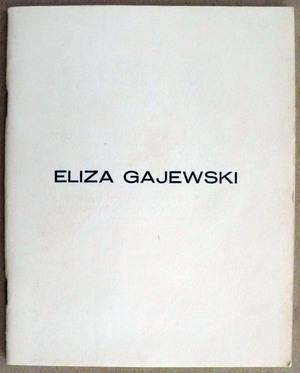

Gajewski and Remont Gallery

Thereafter, Niels Lomholt received more mails from Poland, amongst others, a charming book by Henryk Gajewski "Eliza Gajewski" and a publication from the Workshop of Film Form. In 1974, Gajewski became father of Eliza and on this occasion he published a book with marked places for photos to be taken on subsequent birthdates of his daughter until her adulthood, i.e. until 1992. The places designated for photos were already signed, all that needed to be done was to take pictures at the right time and place, and then send them to the holders of the book asking them to paste photos into the appropriate place. The book was to develop with the artist’s daughter growing up. Unfortunately, Gajewski’s family situation got complicated unexpectedly and the artist sent only the first two photographs of his daughter. Gajewski was very active in the latter part the 70s. He ran Remont Gallery in the student club Riviera-Remont. He organized large international conferences on contextual art (Art as Activity in the Context of Reality, 1977), performance art (International Artists Meeting – I am, 1978), art books (Other Book for Child, 1979), alternative education (Child as an author, 1981). Gajewski organized concerts, issued punk music cassettes and fanzine "PostRemont" (1980) addressed to young audiences. Later, after he had left Poland, he dealt with networking, i.e. connecting people through disinterested exchange with the use of mailart network.

The publication of the Workshop of Film Form informed about the Polish independent cinema, i.e. films by Wojciech Bruszewski, Józef Robakowski or Ryszard Waśko.

Sosnowski and Współczesna Gallery

In 1975, Zdzisław Sosnowski from Współczesna gallery (Contemporary Art Gallery) based in Warsaw established a contact with Lomholt. Sosnowski was a co-founder of Gallery of Actual Art operating in Wrocław in 1972-1974, then he moved to Warsaw where he ran Współczesna Gallery (1974-1977), and later Studio Gallery (1978-1981). Sosnowski was interested in exchanging information with Lomholt as the gallery ran by him published a newspaper on the contemporary art. Sosnowski and slightly younger Gajewski were fascinated with Klaus Groh, who in 1972 initiated the IAC-Info, i.e. cheap, photocopied information leaflet on artistic events edited by the International Artists' Cooperation, that is by artists themselves. Gajewski published Art Texts, a series of books about the contemporary art and culture of well-known artists and critics - Jan Świdziński, Zbigniew Dłubak (in 1977), Jan S. Wojciechowski, Joseph Kosuth (in 1978), while Sosnowski published a magazine modeled after the early "Flash Art" of Giancarlo Politi.

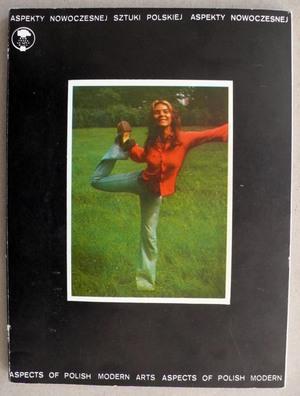

Współczesna Gallery promoted the post-conceptual art making use of mechanical recording means, i.e. photography and film. In September 1975, the gallery organized the exhibition entitled "Aspects of the Contemporary Polish Art", which hosted artists collaborating with it: Jan Berdyszak, Wojciech Bruszewski, Zbigniew Dłubak, Janusz Haka, Andrzej Lachowicz, Natalia LL, Roman Opałka, Andrzej Partum, Józef Robakowski, Kajetan Sosnowski, Zdzisław Sosnowski, Ryszard Waśko, Ryszard Winiarski, Jan S. Wojciechowski. It was a kind of representation of the Polish neo-avantgarde art. At this exhibition Sosnowski showed his first works from the "Goalkeeper" cycle (1975-1977). It was to be a photo-film story about the idol of mass culture, combining the features of a football player, singer and actor. Sosnowski, as a goalkeeper, wearing always a white suit, dark hat, tinted glasses and with a cigar in his mouth, was defending a goal or was desperately fighting for a ball with a young woman attacking him. The combination of shots of the football pitch with shots the goalkeeper wrapping around women's legs, exposing the woman’s high heels ramming into the body of the man, created a little absurd sexualization of the football idol – absurd, if we remember that inspiration for Sosnowski stemmed from the cult surrounding the football national team which won the third place in the world championship in Germany in 1974.

The "Goalkeeper" became the best-known work by Sosnowski. After years, the artist returned to his hero and Poznań gallery Piekary published a beautiful book "Goalkeeper Forever" (2009). The artist once again played the role of the goalkeeper, fighting on the pitch and in private life. This time, the photographs were accompanied by a quite complex and more personal story of a Polish goalkeeper, who in his thirties, as Sosnowski, left the country to play in West European clubs.

Anna Kutera, Romuald Kutera and Lech Mrożek, young artists forming the Wrocław-based Gallery of the Recent Art sent their catalogues to Lomholt in 1975. They also wanted to be a point of the international artistic exchange network.

Petasz and ”Commonpress”

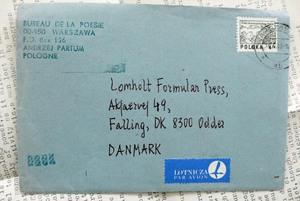

The latter part of the 70s saw intensive correspondence of Andrzej Partum, Andrzej Wielgosz and Paweł Petasz with Lomholt. Partum sent to Lomholt his manifestos: "Criticosystem of Art", "Art Pro/la", "Animal Manifesto", "Manifesto of the Insolent Art". These texts required contexstualization as "Animal Manifesto" printed on the poster of the 18th Meeting of Artists, Scientists and Art Theorists held in Osieki in 1980. Another example of the incisive contextualization was the banner hung over Krakowskie Przedmieście in Warsaw, between the University and the Academy of Fine Arts, with words "Milczenie awangardowe” "(The Vanguard Silence, 1974). Wielgosz promoted the idea of drawing activity, while Petasz specialized in rubber stamp art. In 1978, using rubber stamps and a children printer, he published the book "Ten Theses. Art Theory Series”. Petasz’s publication was the opposite of Kostołowski’s book – in the case of the latter we had to do with modernly designed print, while in the case of Petasz with a coarse, hand-made samizdat in 50 copies. Both publications differed not only visually but also substantively – the time of meta-artistic reflection was slowly becoming a thing of the past. Petasz wrote in a similar tone, but with greater distance and irony; "If art is a crown of intellect, any theory or reflection is possible in art language only” (thesis 0), and a few pages later - "Ideal situation: everyone is artist, everyone is receiver." (thesis 9). And finally, “The general aim of art is to develop notion: human being.” (thesis 10).

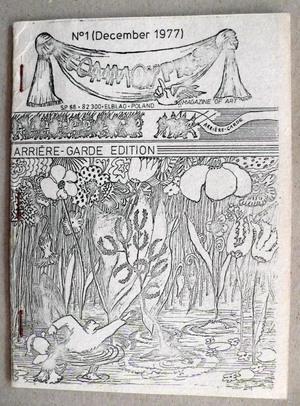

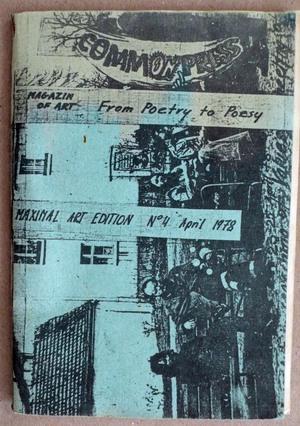

Petasz was viewed as one of the creators of the new genre - the rubberstamp art . He showed his stamp works in the Stempelplaats gallery in Amsterdam in 1978, but undoubtedly his greatest achievement had been “Commonpress" - a joint magazine of mail artists. Petasz was the initiator and editor of the first issue of "Commonpress", which was first published in December 1977. The first issue (untitled) contained works from 17 contributors, the second one ("Open & Closed", March 1978) from 34 artists and the fourth one ("From Poetry to Poesy", April 1978) – from 39. By the end of 1984, there were published ca. 50 issues of "Commonpress", each one edited in different place and by a different author.

Piotrowski (Ukiyo) and Black Market

In 1981, Lomholt received a set of Łódź Kaliska catalogues and in 1982 the first, cherished books by Zygmunt Piotrowski, who also signs his works as Ukiyo, "Dialectics Project" and "Art as Cognition". Activities of Łódź Kaliska were directed against dignity (blast) of analytical art, against the endless analysis of the photographic medium. Instead of the analysis, the group proposed fun, prank, joke, return to the crazy spirit of Dada. Łódź Kaliska heralded the artistic climate of the 1980s. Piotrowski-Ukiyo referred to the theater tradition, the spiritual and bodily exercises of Jerzy Grotowski and the wisdom of the Far East - "How to Touch Nothing". Art should be a tool for cognition, searching for some deeper world order. "All our philosophy has its origin in poetry," claimed Piotrowski and this means that philosophy is another version of poetry and, therefore, there is no essential difference between art and theory. "To guard the self-identity of the human being; isn’t it the hidden matter of art? "In 1986, Piotrowski formed an international group of performers Black Market which traveled around Europe performing in different cities.

Wrap-up

Niels Lomholt’s archives contain three types of documents;

a) private correspondence from Polish artists, critics and art theorists, usually concerning artistic issues, the planned exhibition of Polish artists in Aarhus, Lomholt’s arrival to Poland, thanks and requests for books, catalogues, borrowing films for exhibitions, etc.

b) invitations, catalogues, books, information leaflets and other prints published by galleries,

c) art pieces.

This division seems to be seemingly obvious; art (point c), documentation of art (point b), the non-artistic activities supporting art (point a). In many cases, however, it is not sustainable. Often, in fact, the envelopes themselves can be artistic; postage stamps, stickers, rubber stamps combined with rubber stamps and stickers of artists, their drawings, language games, own slogans creating thus more or less interesting collages. The visual attractiveness of an envelope is enhanced if the artist uses the envelope used previously by someone else once again, as Paweł Petasz and Tomasz Schulz did - cross out the previous addressee, write a new one and add new stamps, drawings and slogans to the earlier envelop. Schulz called it a "round trip" - the same envelope travels from a sender to a an addressee and after some time, it returns to the sender.

Visual attractiveness, however, is not an absolute indicator of art. The envelope can attract attention, it can be arty, but it does not have to be art. Conceptualism made us sensitive to this difference, and mail art deepened it even further. Lomholt writes about mailart that it is easy: "You produce something, post it, and get a response.” For Lomholt mail art was never a new artistic movement, new “ism”, nor a new form of art like happening, but a relatively cheap and convenient way of communication and if so, in extreme cases (a phone call) could do without any material objects. Objects only document the communication process, and therefore they are less important than the process itself, says Guy Bleus. Hence, we can say that in a way, all mail art objects are documentation, documentation of someone's communication activity.

“For those who devote themselves to the production of art documentation rather than of artworks, art is identical to life, because life is essentially a pure activity that does not lead to any end result.", writes Boris Groys and further states: "Art becomes a life form, whereas the artwork becomes non-art, a mere documentation of this life form." As in the case of Wacław Ropiecki "Through art to life." Seen from this perspective, one could say that all the items collected in the Lomholt’s archive are the documentation of one's activity, one's life form.

Lev Manovich compiles databases (databases), i.e. contemporary archives with narratives and asks about the place and role of these two opposing ways of organizing data and assigning meanings to them in the today's computer culture. Do databases replace the old, respected narratives and become an inexhaustible source of new narratives? What narratives can be built based on the Lomholt’s archive? Lomholt organized his mail art archive using the national, or actually, a state key (it reminds of Ko de Jonge phrase: what is yours art key). The exception is the United States where he applied the media criterion - books, magazines, postcards, envelopes. Thus, he encouraged us to build national narratives. One of them could be the story about the Polish alternative stage, which in opposition to the official stage, developed its own information network, tried to join the international debate on art and work out new post-conceptual understanding of art.