Memo from a Networker

By Vittore Baroni

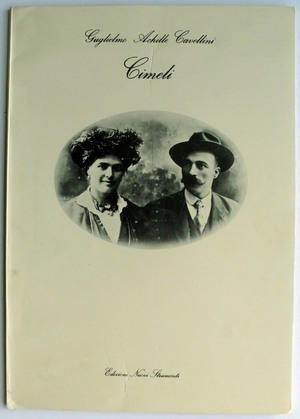

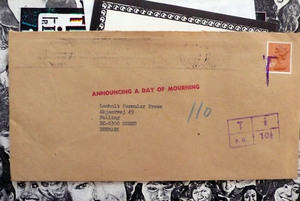

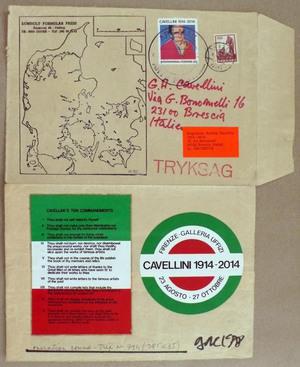

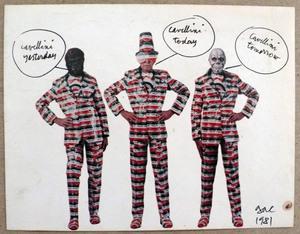

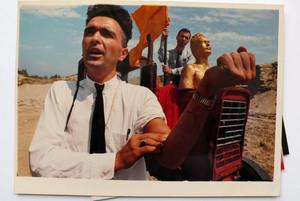

To explain my life-long obsession with the postal system, I usually start from the reminiscences of my personal mail art epiphany, the fortuitous meeting in 1977 with the eccentric Italian artist and art collector Guglielmo Achille Cavellini, facilitated by an advertisement found in an art magazine (fact: G.A.C. was on the reverse cover of “Flash Art” no. 76/77, July-August 1977). Cavellini promised free copies of his own publications to anyone who would contact him, and being a Capricorn I jumped at the chance. I got in touch and, in truth, I received much more than a pile of (quite interesting) old catalogues. I soon visited the artist at his spectacular home/museum in Brescia and he inundated me with promotional stickers, more publications, signed artworks and other gifts. I was intrigued by his open generosity towards a total stranger and even more by the subversive concept behind his self-historicization project, infused with Dada-Futurist vigour but also graced by a captivating humour and a great craft. Here was a single man in battle against the entire Official Art World, who wanted to reach the top by writing his own rules. I was impressed, so I decided to investigate further. I picked up a few addresses from mail art catalogues that Cavellini had around his large basement-studio (Ray Johnson, Anna Banana, Buster Cleveland, Genesis P-Orridge, Pauline Smith, Michael Scott, etc.), and I started from there my involvement with the wonderful and mysterious world of Correspondence Art (to quote the title of the seminal anthology of mail art texts edited in 1981 by Michael Crane and Mary Stofflet for Contemporary Arts Press in San Francisco).

It is always very interesting for me to scrutinize the archive of other mail artists because the materials often fill voids in my collection, offer different perspectives on an author’s work or the chance to notice slight variations in a multiple piece that I also received. In the case of Cavellini, for example, I could see for the first time in the Lomholt Mail Art Archive a quite wonderful catalogue of his early “destroyed works”. All of Cavellini’s regular correspondents have received several of his “operazione andata-ritorno” (or “operation round-trip”: GAC did not speak a word of English, so he had collaborators helping him with the translation of all his personal messages, that he had then to copy painstakingly word for word by hand!). These are a wonderful example of “collaborative pieces”. Cavellini in fact intervened with his own colourful stickers, stamps and rubberstamps over the envelopes that he received (sliced open), juxtaposing his work with the calligraphy and mail art traces of his correspondents. Each numbered “round-trip” is therefore a totally different original piece “ready to be framed”, yet the series is very consistent formally and represents at the same time GAC’s self-historicization project and facets of the personality of the receiver. Cavellini mailed out catalogues and booklets (his “home exhibitions") by the thousands, but he also always found the time to send personalized mails, in the form of altered photographs, signed articles from magazines, re-worked leftovers from his larger gallery pieces, even hand-drawn caricatures of his correspondents (at which he was very skilled). All in all Cavellini, whom I had the luck to meet several times, was a perfect teacher and “role model” for my introduction to the world of mail art, a whirlwind of ideas (he had the knack for transforming the smallest daily events into art) who associated unaffectedly individual genius and an utopian collective vision. It might be interesting to point out that I have been in correspondence with 122 of the 183 artists listed in the Lomholt Mail Art Archive. Two thirds of correspondents in common roughly in the period 1979-1983, though we only exchanged a handful of mailings every year, probably means that the global number of mail artists has been often over-estimated. In their introduction to the anthology Correspondence Art, Crane and Stofflet speak of 10-20.000 active contacts, but an estimate of 1000-2000 is maybe closer to the truth.

My affair with Cavellini, a long term friendship that would continue through my association with Carlo Battisti and his Center for Cavellinian Studies in Viareggio, was not anyway my first adventure in Postland. Living in a small provincial town like I did (Forte dei Marmi, a seaside resort near Lucca, Tuscany, on the West Coast of Italy), even in my early days as a snotty school boy I was often forced to use the post office in order to put my hands on certain objects of desire, such as arcane comics magazines not available at the local newsstand (but I also sent out for my Official Beatles Fan Club kit when I was twelve). I was a precocious rock music fan and a compulsive reader and I always had an eclectic “creative” disposition, so I started in my early teens to submit by post - with very little success - poems, reviews, articles and photo reportages to various national comics and music magazines. Being born in 1956, I was a bit too young to have experienced the Summer of Love on rock festival grounds, but I was able to ride on the long tail of the Sixties counterculture, ordering by mail such historical hippie papers as “Oz”, “IT”, “Pianeta Fresco” (this last one now worth a fortune on the collector’s market). I plunged deep into the folk-rock-jazz music maelstrom of the day and published in the early Seventies my early journalistic efforts - dreamy hand-written narratives intermixed with cartoony ink drawings - in “Carta Stampata”, a small alternative magazine published in the nearby town of La Spezia. I developed a pen pal friendship with other contributors to magazines of the fading “Movement”, and through these postal contacts I started to feel part of a wide underground community. At that point, it still seemed possible to produce a drastic change for the better in the course of the Western Civilization, with a little help from a global network of like-minded cultural agitators.

It comes as no surprise, given this countercultural background, that my encounter with mail art resulted in love at first sight. Here was a freewheeling grassroots group of art activists that bypassed all the hierarchical rules and institutionalized bureaucracies of the mainstream art market, to promote instead a direct contact and egalitarian, uncompetitive interchanges. With mail art, “everyone is an artist” finally became not just a slightly hypocritical slogan issued by art gurus like Joseph Beuys, but a daily practice in a planetary network of interconnected mail-boxes, no credentials or membership card requested, no approval needed from art critics, magazine editors or gallery owners. Everyone, even a six years kid, could be a mail artist. Most of all, this New Thing was free, with no products for sale and almost no money involved, just the cost of postage stamps on an envelope (how un-capitalist!). I had a deep dislike then for the traditional Art System, that I saw as too narrow-mindedly middle-class, commercially oriented and helplessly outdated. I could not picture myself as the creator of expensive art pieces for an elite of rich (in)competents. “Art” indeed sounded a bit like a dirty word in those days. When I was about eighteen, in my impudent megalomania I decided that I would not write a novel, as much as I would have loved to, if I could not find a way to move “beyond” James Joyce (fact: all my friends did, but I never wrote one). I also felt that it was pointless to employ my time in the production of art works, if it was not with the aim to progress logically a step further along the paths opened (and sometimes also closed) by Marcel Duchamp, George Maciunas and a handful of other personal art heroes. Mail art seemed to be a good answer to the creative impasse that was starting then to afflict the post-conceptual contemporary art scene, soon prey of the weak thought and the superficial “quotationism” of the Post-Modern age (e.g. the lame neo-Expressionism of the Italian Transavanguardia).

In the second half of the Seventies, when I started to tinker around the underground art scene, I was therefore not interested in the production of art works for gallery shows, but rather in the organization of happenings and social events that could upset the dull daily routine. I turned many high-school parties into wild mixed-media extravaganzas, with live rock music and immersive art installations. At night, I often altered public billboards with satirical messages, just for the fun of it, long before the advent of Adbusters. Mail art - to my eyes not simply a new art movement but a new cultural strategy - was on the same wavelength of those naive early private happenings and of the many “free festivals” that I attended throughout the decade, with the audience as much part of the event as the rock bands playing on stage. I was to learn much later that there were precise subterranean links between mail art and the Sixties counterculture, and even the Beat(nik) literary circles that preceded it. A fitting example - but this would be a fascinating area for a thorough investigation - is Wallace Berman’s “Semina” (1955-1964), a limited edition magazine of art and poetry mostly distributed free, by hand and through the mail, to a circle of friends and authors, a real precursor to the “assembling magazines” so common in the early days of mail art (see Michael Duncan and Kristine McKenna’s Semina Culture: Wallace Berman & His Circle, D.A.P.-Santa Monica Museum of Art 2005). Berman’s mailing list included a certain Ray Johnson, to be soon universally known as an intuitive Pop Art pioneer and the whimsical founding father of mail art. Johnson certainly didn’t single-handedly invent the correspondence art network, but he did put into a new focus the manifold possibilities of a medium that had already been widely employed since the times of Futurism, Dada and Surrealism. With Ray, mail art proved to be not just a sort of sociological phenomenon or an ephemeral collateral activity, but truly an autonomous medium with a specific language, even capable of producing its own masterpieces (starting with Johnson’s poetic collection of textual and visual messages addressed to the Fluxus publisher and theorist Dick Higgins, The Paper Snake, The Something Else Press, New York 1965).

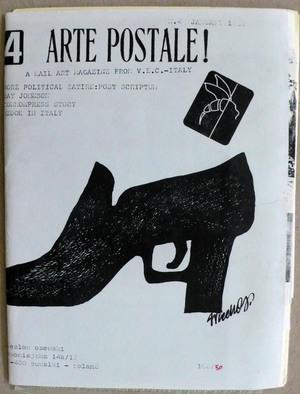

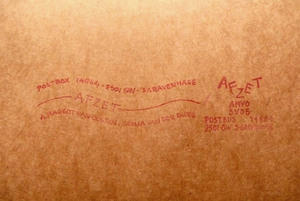

The Lomholt Archive contains a large number of artist’s magazines, including several early issues of my own “Arte Postale!”, one of the longest running mail art publications ever. I simply named my self-produced publication Mail Art with an exclamation mark, to point out the exuberance and warmth of the “Eternal Network”, the name that the Fluxus artist Robert Filliou gave to the postal artists’ network (Filliou, like myself, was born on January 17, and he proclaimed that date “art’s birthday” - incidentally, I mailed my first letter to Niels Lomholt, containing a poster based on that date, on January 17, 1979). In the course of three decades, I published “Arte Postale!” with a very irregular periodicity and circulation, often adopting different formats and sizes. Initially, a new issue appeared almost every month, with a certain cut-and-paste rudeness of design, on the same wave-length of the punk fanzines of the late Seventies. Gradually, the issues became less frequent and more complex in design and format. The first fifty issues of “Arte Postale!” were produced in limited editions of 100 copies, adopting the strategy of “assembling magazines” launched in 1970 in New York by the experimental poet Richard Kostelanetz in his seminal “Assembling” publication (and, before him, also introduced by other poet’s magazines, such as Adriano Spatola’s “Geiger” and Eugenio Miccini’s “Tèchne”). Each participant sent me a hundred copies of a page, postcard, postage stamp or other materials, that I then collected together, adding a cover and a few editorial pages. After issue 50, I discontinued the assembling method and usually produced the entire magazine by myself, in photocopy or off-set, always adding many little manual interventions, so that each copy became a sort of “collector’s item”. Assembling magazine such as those present in the Lomholt Archive (“Afzet”, “Geiger”, “Texto Poetico”, “Data File”, etc.) are particularly important in the preservation of a history of mail art because each issue contains a wide selection of original (and ephemeral) works from international authors. Often these works are not glued or stapled together but simply housed loose inside a cover, an envelope or a bag, so each copy of the magazine can be seen as a little “home exhibition” with pieces ready to be framed and admired. Magazines of all kinds have also proved to be a useful shortcut to introduce mail art to a larger art audience. If the personal work of even the best known mail artists is still largely ignored by art historians, their zines in fact have managed to be included in important recent surveys, exhibitions and books devoted to artists’ publications (such as Artist’s magazines: an alternative space for art by Gwen Allen, The MIT Press 2011).

Underneath the sea all the islands are joined, and also all the (sub)cultures “in opposition” are similarly interconnected. The fracture between the hippie times and the punk era is, for instance, really not as deep as it may seem at first glance. You just have to connect the dots, from Hugo Ball to Guy Debord, from Timothy Leary to William Gibson, from William S. Burroughs to Genesis P-Orridge, from the mimeographed poetry bulletins of the Fifties to the xeroxed fanzines of the late Seventies and so on. My writings about underground experimental music and the rising of new “networking cultures” started to appear on national magazines (“Rockerilla”, “Rumore”, “Velvet”, etc.) as well as in an endless succession of small international fanzines and do-it-yourself publications. I introduced the Italian readers to the noisy and provocative “Industrial music” genre, that had deep roots in the mail art milieu. Members of bands like Cabaret Voltaire, Merzbow, Nocturnal Emissions, etc. had been extremely active in correspondence art at the start of their careers. P-Orridge’s quartet Throbbing Gristle - whose first vinyl album, incidentally, contained forms to be filled and returned by mail - distributed the bulletin “Industrial News”, a seminal source of information and contacts for the so called “tape network”. This was an international circuit of musicians and small tape-labels that produced, sold and exchanged mostly through the mail audio works on cassette, practicing collaborative strategies very akin to mail art (for a history of home-taping and self-released music, see Unofficial Release by Thomas Bey William Bailey, Belsona Books 2012). Different circuits, alternative to the cultural mainstream, really crossed and mingled: the post-Beat poets and the visual poets, neo-Dadaists and neo-Situationists, mail artists and independent d-i-y bands.

So what did make mail art so interesting? Artist-types want to be loved, and the warm direct contact with hundreds of allied individuals worldwide was much more satisfying than the occasional feedback from a few viewers or critics at art exhibitions. The postal network was a totally different experience, not just a marketing tool but a new baptism, the admission into a planetary enlarged family. I was aware, when I sent out my first rough collages and photo-works, that I had lost the “first wave” of correspondence art, spurred by the publication of a handful of seminal articles in the early Seventies (like David Zack’s “An Authentik and Historikal Discourse on the Phenomenon of Mail Art” in the January-February 1973 issue of “Art in America”). And as is evident from the wealth of Zack’s long hand-written and type-written letters, original collages and one-of-a-kind postcards housed in the Lomholt Archive, mail art is a very fleeting and intimate experience, custom built by each author taking into account the distinctive features of each correspondent. You miss a blink (or a letter) and a connection is cut, an entire development in the mail art saga is lost, a whole branch of activities remains unexplored. This is what makes the cataloguing and the online access of mail art archives so important, as new doors are opened to an endless chain of rediscoveries and revaluations.

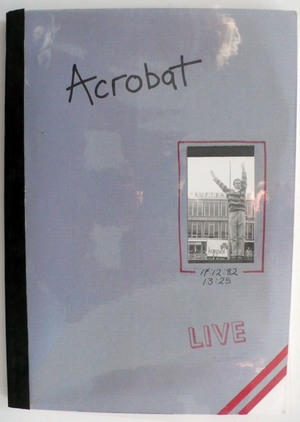

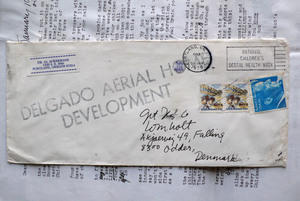

Nevertheless, what I found myself immersed in was a quickly growing international network that was just starting to acquire a sense of identity and purpose, through a diversity of approaches and a great richness of themes, techniques and media: you got the artist’s stamps of imaginary countries and the pseudo-bureaucratic rubber stamps, the hand-made postcards and the illustrated envelopes, the conceptual mailings and the mail sculptures - all very specific, witty and colourful forms of anarchic postal expression - but since in correspondence art “anything goes”, what really made the daily arrival of the postman so thrilling was the libertarian looseness and utter unpredictability of the medium. You could get a dry fish or a flat tire with affixed stamps on a good day, an inflammatory rant or a puzzling collage to be altered and forwarded, a performance on vhs tape or a weird home-made magazine. The most original and adventurously productive period in mail art was the decade between 1975 and 1985, when letters from behind the Iron Curtain or from South American states under a military regime were still a vital outlet for otherwise suppressed and isolated authors. For many, mail art was the only way to let their voice be heard outside the limitations of local censorship. The aim was not just to circulate their own art, but to build a better and more interconnected world. The process of synergies, cooperation and mutual support put into motion was therefore often valued as much as the actual subject and content of the different projects. The medium really was the message.

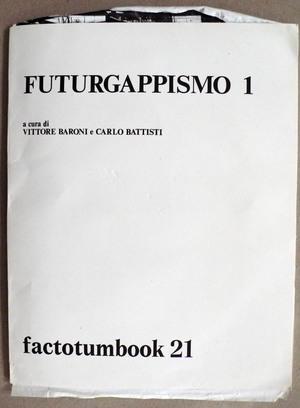

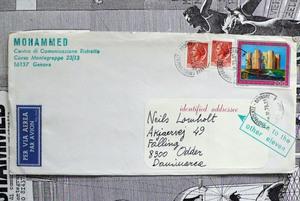

The correspondence exchange proved to be a great school and workshop for a young apprentice who, like me, had never seriously thought about being an “Artist” before. In fact, the term “networker” or network operator was often preferable to the worn out “capital A” term. And after two years of intensive postal activities I thought I needed a magazine to trade materials more easily with a growing list of contacts, so I started to assemble the already mentioned “Arte Postale!”. Though also available at a regular (very low) price to the general public, my postal magazine has been mostly exchanged free of charge with similar publications from other mail artists, in the true open and “no profit” spirit of mail art. The magazine was also mailed, usually free of charge, to selected archives, museums and libraries world-wide. The copies of “Arte Postale!” in the Lomholt Archive (according to my own files, I sent issues 2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 14, 37) are particularly rare, as they all belong to the early “assembling” period limited to 100 numbered copies, with original pieces from authors that have become legends in the mail art annals. In 1980 I gave birth to Lieutenant Murnau, a ghost band that was both a “multiple name” - in the vein of Monty Cantsin, the Open Pop Star of Neoism - and a collective experiment in sound recycling. Then I joined forces with the artist-photographer Piermario Ciani and the comics artist Massimo Giacon to give life in 1981 to the international group TRAX in my mind an evolution of mail art strategies intersected with Maciunas’ vision of “Flux Kits” as collective multimedia products with an accessible price. But while Maciunas was still the boss of his circuit of artists, always trying to reconcile and discipline the many contrasting egos, the “TRAX modular system” was based on a more democratic and flexible concept. Each participant could decide to become a “Central Unit” and create a TRAX product or event, requesting the collaboration of a variable number of “Peripheral Units”. It was a (sub)network with many heads, that mixed mail art and d-i-y music contacts with comics artists and a wide range of “mad scientists” of the underground. When in 1987 we decided to terminate the experience, the final book-catalogue Last TRAX included a list of the over 500 participants to almost a hundred different projects and publications (fact: Niels Lomholt took part in the cassette-magazine TRAX 1085 Neoist Ghosts). By the way, inspecting the Italian works in the Lomholt Archive, I was able to learn from a message/invite dated 1981 about a plan for a (failed) project by a TRAX member, Giancarlo Martina, that I had never heard of before (Magatrax, a series of retouched porno magazines from around the world!). With so many fake or real art movements and group projects in its ranks (Neoism, Plagiarism, Futurgappism, Spiegelmism, Impossibilism, TRAX, Plinio Mesciulam’s Mohammed system, Ruud Janssen’s IUOMA - International Union Of Mail-Artists, Robin Crozier’s collection of collective memories (Memo)Random, Ryosuke Cohen’s communal prints Brain Cells, etc.), mail art can be veritably thought of as a large constellation made up of a number of smaller and intersecting networks.

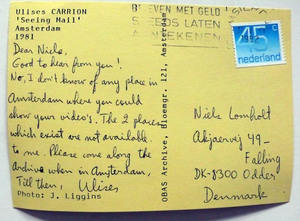

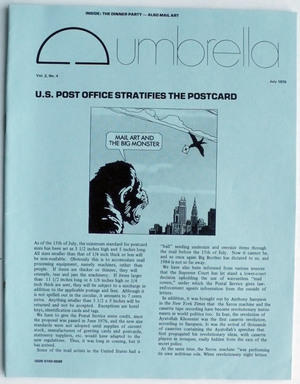

While my knowledge of the postal network grew exponentially through exhibitions and projects that involved hundreds of authors, I noticed that there were just a few isolated voices (the art curators Jean-Marc Poinsot and Hervé Fischer, Ulises Carrion with his Amsterdam bookshop/gallery Other Books and So, Judith A. Hoffberg with her “Umbrella” magazine, professor Craig J. Saper…) who tried to introduce to a more general public the amazing planetary experience of the Eternal Network. A side effect of the truth that mail art moved no monetary interests - being a process not a product, a gift instead of a commodity - was the fact that it moved no academic or scholarly interests either (guess why!). I felt the need to synthesize the peculiarities of the mail art process and of “creative networking” in a couple of simple educational graphic schemes, that were widely reproduced in postal magazines and catalogues. In the broadsheet “Real Correspondence Six” (1981) I saw the networker as a new cultural figure, a sort of meta-author who created contexts for collective expression rather than conventional individual works, and whose activities eluded the “vicious circle” of the art market and therefore needed new critical parameters and instruments to be fully analysed and understood. In the “Organic Tree of Networking” (1992) I tried to represent the ramifications in different media of the networking practice and its various roots, from Dada to Situationism. When in 1995 I founded with Piermario Ciani the small publishing house AAA Editions, the most natural thing to do was to write my own “guide to the network of creative correspondence” (Arte Postale, AAA, Bertiolo 1997), trying to provide a complete overview of the phenomenon. The book was followed by other more specific essays devoted to Rubber Stamp Art (John Held Jr., AAA 1999), Artistamps (James Warren Felter, AAA 2000) and Postcarts (Vittore Baroni, AAA/Coniglio Editore 2005). In absence of sympathetic professional art critics and of a real interest from academic circles, the mail artists had to take on themselves the burden to accomplish the ground work, writing fundamental text-books such as John Held Jr.’s Mail Art: An Annotated Bibliography (The Scarecrow Press, Metuchen/London 1991) and Chuck Welch’s Eternal Network: A Mail Art Anthology (University of Calgary Press, Calgary 1995). Things have not changed much in four decades, and today it is still the network that has to pay homage to its prime-movers (case in point is Amazing Letters, a retrospective about “The Life and Art of David Zack” edited by mail art veteran Istvan Kantor, The New Gallery Press, Calgary 2010).

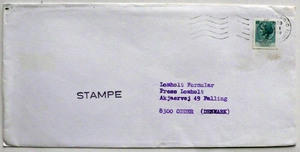

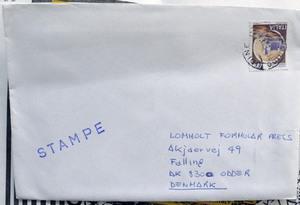

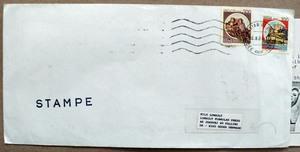

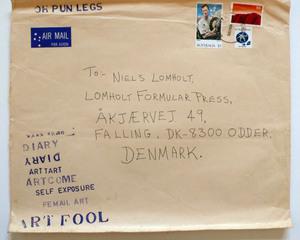

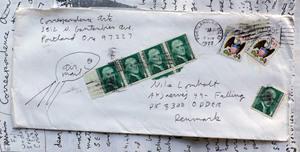

Practicing mail art and corresponding with literally hundreds of contacts with a daily flow of letters and packages, after a while certain patterns began to emerge. To answer all the requests that arrived from the different corners of the world became a sort of sport training, a mental challenge, a Zen activity. You started to recognize the personal style and character of each correspondent, distinguishing those who made extensive use of artist’s stamps from those who favoured the medium of rubber stamps or postcards, those who would always enclose a hand-written message and those who just let the work speak by itself. There were postal items that lent themselves to be collected, framed or carefully stored, others that requested a collaboration, that were made to be altered, recycled and returned to the sender or to be forwarded as chain-letters. Niels Lomholt’s forms to be filled and returned (from Lomholt Formular Press in Odder, Denmark) were a particularly mysterious variation on the popular “add to and return” brand of mail art, practiced intensively (if not invented) by Ray Johnson himself. Lomholt’s forms were printed in various colours on light pink, yellow or white UniA4 sheets, with a baffling mixture of graphics, photos and quite strange requests and themes that referenced “spinning eyeballs” and masturbation, textures and fragments, a “Mr. Klein” falling from a window and a “organized coincidence” of “exchangeable photos”. Sometimes you would alter and forward a bit reluctantly these beautiful pages, but we all instinctively understood the importance of art as a collective and reciprocal test. In those days, the mail art beehive buzzed with ideas and was just searching by trial and error to reach a certain level of osmosis, to build an organic albeit flexible structure. Each one of us was a unique mythopoetic piece in the Eternal Puzzle.

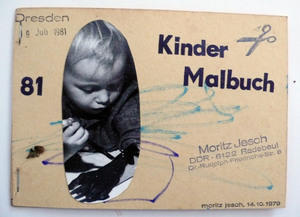

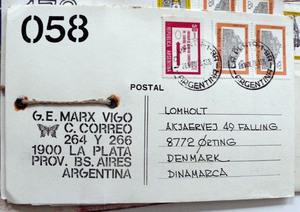

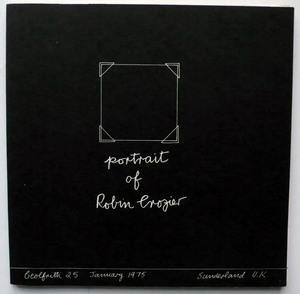

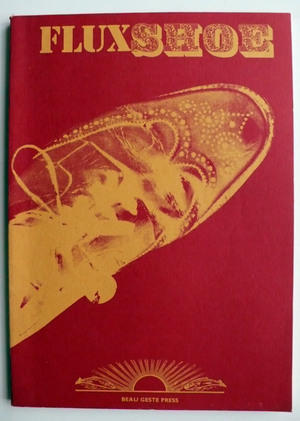

There were militant mail artists who, if you entered the network in the Eighties, you would have found very difficult not to stumble into, colourful and inspiring figures like G.A. Cavellini and David Zack, Pat Larter and Al “The Blaster” Ackerman (all sadly no more with us), Anna Banana and Clemente Padin, Rod “V.E.C.” Summers and Guy Bleus, all well represented inside the Lomholt Archive. With “militant” mail artist I imply authors that did not simply utilize the postal network to disseminate their creations but who also cared about the growth of the “community spirit” of the network, who tried to define the very nature of correspondence art and to put under test the limits of the medium. For example, think of the postcards and envelopes sent from behind the Iron Curtain by artists that risked on their own skin, often intercepted by the State Police, to spread messages of political freedom, pacifism, ecological awareness and “art in contact” (Joseph Huber, Robert Rehfeldt, Birger Jesch, etc.). Or think of such an iconic piece as the 1978 Jail postcard from Argentina - also in the Lomholt Archive - by G.E. Marx Vigo (a pseudonym used by the combined Graciela G. Marx and Edgardo A. Vigo), with the word “Jail” in black capital letters on the image side and a folded strip tied by a piece of rope: if you untied the rope, the strip revealed the red word “Free” in capital letters, at the same time a confrontational political statement (Vigo’s son was among the desaparecidos) and a work that technically pushed the limits of what could be considered a postcard. Certain authors, like the British teacher and artist in a post-Fluxus vein Robin Crozier, bravely redefined at each new project the rules and standards of postal collaboration, showing an enormous dedication to networking as an art in itself. Think of Crozier’s unique collective booklets based on precise requests (for the on-going series Views, for example he asked a view of a town nearby to where the contact lived, activating a psycho-geographical process) or of his catalogues with neat re-drawing (Portrait of Robin Crozier, 1975) or hand-written description (Blue, 1978) of each piece he received, instead of the usual photographical reproduction, stressing how personal a collective mail art project could remain. A piece in the Lomholt Archive is quite representative of the quirky humour and homely craft involved in Crozier’s mail, as well as being a fine example of the odd surprises that a mail artist could find every day in his/her mailbox: a life-size crutch knitted in green wool, titled The Chris Crozier Order of the Soft Crutch. The Lomholt Archive, covering a good slice of the Golden Era of postal art, contains a large number of “mail art defining” publications and small masterpieces, such as Anna Banana’s “Vile” magazine and associated ephemera (a seminal influence on the first wave of punk zines), the milestone FluxShoe catalogue (I’d give a hand for one!), artistamps from initiators of the genre (Ed Higgins, Ed Varney, Russell Butler), drafts and chapters of Zack’s Correspondence Novels, founding materials from prime-movers of Neoism Istvan Kantor, Pete Horobin, “restricted communications” from Plinio Mesciulam’s historical copy art/networking project Mohammed, etc. etc.

Every mail artist spun around him/herself a web of contacts that was a unique mixture of personal friends, hardcore correspondents and casual contacts, so the mail art world looked really quite different from each point of observation. And then there were the actual face to face encounters. Mail art has never been a practice for reclusive loners: you established connections, made friends, visited them or met them at mail art events, festivals and conventions (such as the renowned Decca-Dance in Hollywood of 1974, or the “Decentralized WorldWide Congresses” of 1986 and 1992). Many years before Swiss artist H.R. Fricker adopted the term Tourism for his visits to other networkers, there was an irregular but steady subterranean current of networkers visiting each other. When I was still living with my parents, my mother was always ready to add a plate on the table for one of these odd characters regularly showing up, mostly unannounced, on our doorstep. Then in the Nineties the mail art network started to run a bit in circles, it became a well codified game (invite > show > catalogue), losing its utopian edge together with the novelty factor. The crazy restlessness, the urge to drop anarchic creative bombs into the art establishment machine were gone. Instead of resembling a conspiracy of art rebels and loony outsiders, some mail art groups started to look more like tea clubs for old ladies interested in the creation of cute greeting cards (or harmless “ATCs”, see books like Patricia Bolton’s 1000 Artist Trading Cards, Quarry, Gloucester 2007) rather than storming the world with subversive art theories. Many networkers migrated at this point to the expanding frontier of the Internet, following a path “from counterculture to cyberculture” similar to Steward Brand’s jump from the paper versions of his Whole Earth Catalog to the virtual communities of The WELL Bulletin Board System. This transition from analogue to digital mail has facilitated a revaluation of mail art not as an art form per se but rather as a “precursor to Art and Activism on the Internet” (see Annemarie Chandler and Norie Neumark’s anthology of essays At A Distance, The MIT Press, Cambridge/London 2005 or Tatiana Bazzichelli’s Networking: The Net as Artwork, Digital Aesthetics Research Center, Aarhus 2008). Therefore, the prevailing perception of mail art by the general public is today somewhat schizophrenic: on one side it is seen as a collaborative, inexpensive and playful art form bordering with philatelic nostalgia and the cosy world of homely crafts (as described in how-to guides such as Karine Brosse’s Découvrez l’art postal, CréaPassions, Limoges 2007, or Jennie Hinchcliff and Carolee Gilligan Wheeler’s Good Mail Day, Quarry Books, Beverly 2009), on the other side correspondence art is viewed as a prescient forerunner of today’s “social networks” and a source of inspiration for new generations of net artists and hacktivists (fact: in 2013 I was invited to organize in Berlin a collective mail art project through a system of pneumatic post for the transmediale festival of digital arts and culture, PNEUMAtic circUS, short-circuiting a meeting of physical mail and new technologies).

So what? It has been for me a long and interesting rollercoaster ride, the whole 35 years of it, with always a towering pile of correspondence to be answered and never a dull moment. I do not regret all the energies and the enormous amount of time (and money) that went into my mail art obsession, it surely enriched my life and it also gave me quite a few gratifications (fact: the complete 100 issues run of my “Arte Postale!” magazine is preserved in prestigious institutions and archives such as the MaRT museum in Rovereto, Italy and The Ruth and Marvin Sackner Archive of Concrete and Visual Poetry in Miami, USA). I have now 3000 Facebook “friends”, I can reach many of them simultaneously in a few seconds and receive instant replies, but the quality of the communication and of the networking experience is something quite different from the “snail mail” I exchanged for years with thousands of networkers. There is no more an “underground” culture today but rather a “liquid” one, with everything easily accessible to everyone online. Yet, it looks like our wild utopian schemes have been compressed into a small bird cage, from which we are only allowed to emit feeble tweets. In the heart of mail art maybe resides the secret for more complete, empathetic, effective forms of networking than those pertaining to what the social media critic Geert Lovink has called in a recent book Networks Without a Cause (Polity Press, Cambridge 2011). The mail art network had many shortcomings, but for sure there was a sense of fighting for a common cause. It is of basic importance that those who lived it in person try to preserve the authentic history of the Eternal Network in every possible way, in print as well as in virtual data banks (fact: the English Wikipedia page on “Mail Art” was created as a collective entry by Keith Bates and myself with the assistance of a group of international mail art veterans). As Niels Peter Lomholt’s book Lomholt Mail Art Archive, Fotowerke and Video Work (Lomholt Formular Press, Denmark 2010) attests, serious studies on the wealth of materials contained in mail art archives world-wide are just starting to surface. We need more illuminated networkers aware, just like Lomholt, of the significance of what they accomplished in the Golden Age of mail art and ready to roll up their sleeves and again carry out the hard scholarly work. The world is still waiting for the ultimate reference book on this truly remarkable and still much underestimated subject.