The Net Out of Control:

Mail Art in Latin America

By Fabiane Pianowski

Mail art is like the history

of unwritten history.Paulo Bruscky 1976

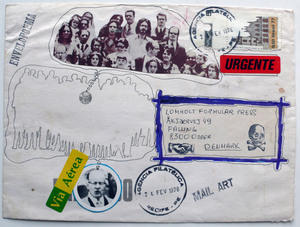

Breaking away from the official circuits of art galleries and museums, mail art heralds a new era for the circulation of artistic work, which focuses primarily on the collective. This alternative means of circulation for artistic proposals and ideas, brings forward the concept of network that would later with the birth of the Internet, become a highly significant issue for contemporaneity. Many conceptual artists developed pieces using networks destined for the circulation of goods and services as their medium, and thus gave visibility to the notions of network and circuit, which are by definition abstract and invisible.

In the 1970s, some critics and art historians considered mail art as one of the great phenomena of the international avant-garde. In its broadest sense, its actions, according to Walter Zanini (1985) - an important art critic and historian in the Brazilian context - enabled the new artistic languages to trigger communicational and structural situations, such as for example, disobjectivation and anonymity.

The use of mail in the 1960s and 1970s, as a tactical instrument in the field of art relates to the appropriation of the means of communication by the period’s artistic manifestations. A period in which establishing networks and communicating were crucial cultural elements.

The goal of the artists was to break away from media’s one-way emitter-receiver flow, through the spectators’ active participation in the piece itself. This would socialize authorship and dilute the borders that divide the artist and the public. In so doing, mail art democratises art.

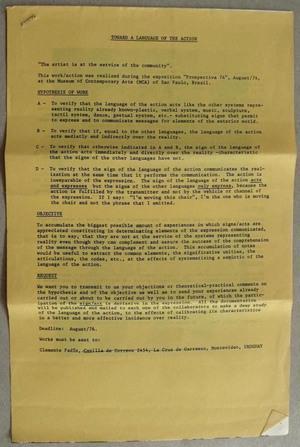

Mail art is a collection of varied aesthetics, whose means of expression is through official mail. Mail art appropriates this means of expression in a subversive manner to configure an alternative cultural channel for the exchange of artistic messages. The function of mail art as a network for subversive communication, added to the period’s social context, pushed it to adopt a critical stance, together with Fluxus and Situationism, aimed at revealing the oppressive and absurd conditions imposed by the social medium. According to Gache (2005), the repressive context of dictatorship enabled the surfacing of mail art in Latin America. In this perspective, she adds, “in the 1960s and 1970s, mail art emerged as an activity strongly linked to resistance against the political and cultural repression that engulfed the continent” (p.42).

According to Freire (1999, p.78), mail art in Latin American and Eastern European countries represented the acceleration and opening-up towards artistic contents that circulated beyond these countries. Furthermore, it permitted the exchange of ethical-aesthetic information, which in the repressive context of dictatorship became an effective subversive strategy, often articulated, through essentially political contents. As Paulo Bruscky points out, “in mail art, art recovers its main functions: information, protest and condemnation” (Bruscky, 1985, p. 77)

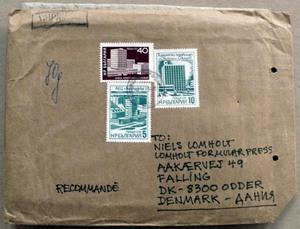

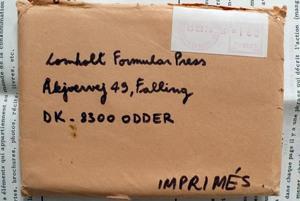

Mail turned out to be a highly effective medium for the transmission of subversive messages, given the complexity of effectively controlling the enormous daily flow of sent and received correspondence. In order to defeat censorship, many postal artists also ciphered their messages, using visual poetry as an efficient means to transmit subversive messages. Therefore, in the Latin American context, mail art became a valuable means of communication with the outside world. Stamps, seals and slogans inserted into regular mail, condemned situations of oppression, torture and humiliation as experienced on the continent.

Some postal artists were imprisoned for organising controversial international exhibitions or for the protest and dissent expressed in their correspondence. This political and ideological activity within the network greatly discomforted repressive government’s censorship, as Paulo Bruscky explains:

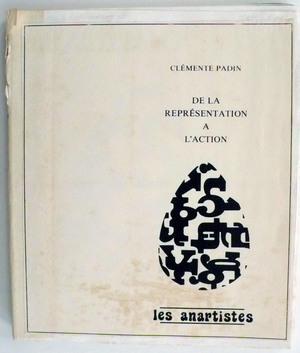

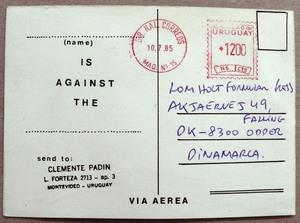

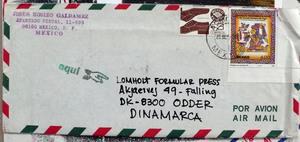

Beyond the problems caused by an outdated postal bureaucracy, the added problem of censorship is almost exclusive to Latin America. This lead, for example, to the closure, minutes after its inauguration on the 27th of August 1976, of the Second International Mail Art Exhibition, in the vestibule of the Central Post Office in Recife (Brazil), who incidentally promoted the exhibition. Twenty-one countries were represented with 3,000 works of art, but only a few dozen people were able to view them. Not only did they close down the exhibition, Brazilian mail artists Paulo Bruscky and Daniel Santiago, who organised the event, were imprisoned for three days. They released the pieces after a month, and apart from the inflicted damages, various works of art from Brazilian and foreign artists are to this day still confiscated. Another absurd event within the dynamics of “cultural repression” in Latin America was the imprisonment by the Uruguayan government of mail artists Clemente Padín and Jorge Caraballo between 1977 and 1982. In April 1981, the military dictatorship in El Salvador kidnapped mail artist Jesús Galdamez Escobar, only avoiding assassination by fleeing and seeking exile in Mexico. It is always the same; those who pretend to “own culture” will always try to impose their methods. (Bruscky, 1985, p. 77)

The mail art network has often associated with social movements, such as international amnesty committees. This channel permitted the condemnation of several imprisonments, putting pressure on dictatorial governments, and obtaining, in some cases, the liberation of prisoners before the end of their prison sentences. Clemente Padín, for example, attributes his early release to the international protests of other mail artists with whom he maintained correspondence.

Another way of outwitting the system is to use pseudonyms or collective monikers. These practices originate in use of noms de guerre within the realm of revolutionary tactics. There is nothing new in the use of pseudonyms to guarantee anonymity in the art world. Duchamp, for example, employed pseudonyms in more than one occasion, signing pieces under the names of R.Mutt or Rrose Sélavy. Beyond criticising the defence of the alleged ownership of ideas that capitalist society sustains, together with the notion of copyright, we can also find, underlying this practice, and given the repressive political context, the aim of granting invisibility to the authors, placing them, therefore beyond the reach of the oppressors.

Mail Art in Latin America

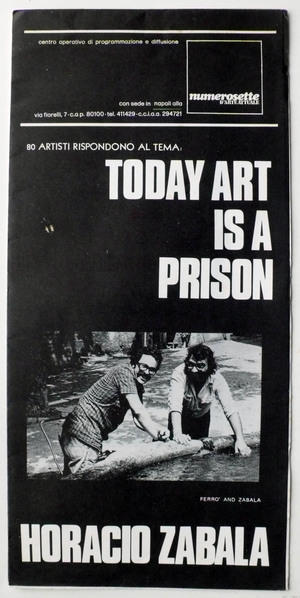

The first manifestations of mail art appear in Latin America at the end of the 1960s. Its forerunners in Argentina are: Edgardo Antonio Vigo (1927-1991), Horacio Zabala (1943), Liliana Porter (1941) and Juan Carlos Romero (1931); in Uruguay, Clemente Padín (1939) and Luis Camnitzer (1937); in Chile, Guillermo Deisler (1940); and Pedro Lyra (1949), Paulo Bruscky (1949), Ypiranga Filho (1936) and Daniel Santiago (1939), in Brazil.

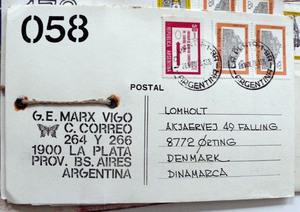

Nonetheless, the movement did not establish itself firmly on the continent until 1974. In that year, Montevideo hosted the Festival de la Postal Creativa – the first documented mail art exhibition in Latin America. Since then, numerous expositions are organised, as in Argentina with the Última Exposición Internacional de Arte Postal (La Plata, 1975), organised by Edgardo Antonio Vigo and Horacio Zabala.

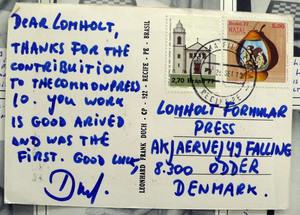

In Brazil, the Primeira Internacional de Arte Postal, held in São Paulo in September 1975, and organised by Ismael Assumpção, represents the first exhibition of this art form in the country. The event was restricted to internationally recognised practitioners in contact with the organiser. In December, that same year, the Primeira Exposição Internacional de Arte Postal (Recife, Pernambuco, 1975) was organised by Paulo Bruscky and Ypiranga Filho. This event was highly significant as it involved a large number of artists, and because it was held in the vestibule of a public hospital, a very unusual venue for artistic exhibitions. In 1976, Paulo Bruscky and Daniel Santiago organised the Exibição Internacional de Arte Postal (Recife).

The violent repression that characterised the successive military regimes that were in power in various Latin American countries marked the political context in which these manifestations took place. Censorship, imposed ideologically through the control of information and cultural production, became the main instrument of social control in these regimes. As a result, a culture of protest marked this period, pushing art, in its many manifestations, to commit itself with social change. In the end, “art had a practical value, building awareness among the people, summoning them to fight for, and condemn, the realities of the disadvantaged peoples” (Stephanou, 2001, p. 139).

Mail art, together with other artistic manifestations were severely repressed during the dictatorial period, as art was the ground from where opposition against the regime would emerge. Clemente Padín confirms this:

[...] when a dictatorship establishes itself, the poets are the first to be imprisoned. Why? Because they force people to choose, to opt between different options and this kind of behaviour seeps through all human conduct. It is impossible to impose rules on those who are used to choice (Padín in a interview to Leão)

In this period, mail art focused exclusively on condemning the oppressive system, for which its practitioners paid a very high price. The military banned the 1976, the Exposição Internacional de Arte Postal in Brazil, ordering its closure an hour after its inauguration and imprisoning its organisers. This had international repercussions, showing the power of dictatorial repression to the world, as well as the reasons behind Latin American artists’ commitment to fight and condemn such practices from that day onwards. Added to this unfortunate event, various postal artists throughout Latin America, such as: Jorge Caraballo, Clemente Padín, Jesús Romeo Galdamez and Guillermo Deisler, among others, were arrested and tortured by the repressive and arbitrary system. Furthermore, these forces also led to the disappearance of Paulo Vigo, son of the Argentinean postal artist Edgardo Vigo.

According to Gerardo Yépiz, despite the fact that in other parts of the world mail art succumbed to trivialisation and even commercialisation, in Latin American countries, local specificities and traditions gave this manifestation a particular nature in terms of struggle and condemnation. According to the author, we must add this to the effort of these peoples to strive for better and more humane living conditions, to obtain peace and social justice. Therefore, mail art wields significant power, and develops an intense activity in Latin American countries.

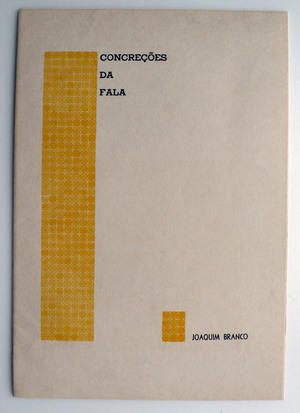

In the 1970s, that is to say, in the first phase of Latin American mail art, the more significant postal artists in Brazil were, Pedro Lyra, Joaquim Branco, U. Lisboa, Paulo Bruscky, Samaral, Julio Plaza, Avelino de Araújo, Daniel Santiago, L. M. Andrade, Leonhard Frank Duch and Odair Magalhães. In Argentina we can name, Edgardo Antonio Vigo, Horacio Zabala, Carlos Ginzburg, Graciela Gutierrez Marx, Juan Carlos Romero, Luis Iurcovich, Luis Catriel and Luis Pazos. As well as the Chilean Guillermo Deisler (exiled in Germany) and the Uruguayans Clemente Padín, Haroldo Gonzáles and Jorge Caraballo.

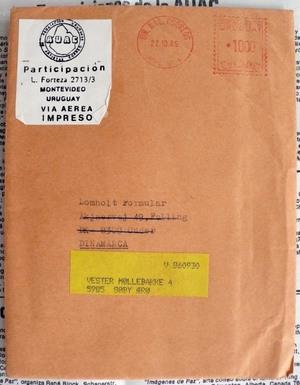

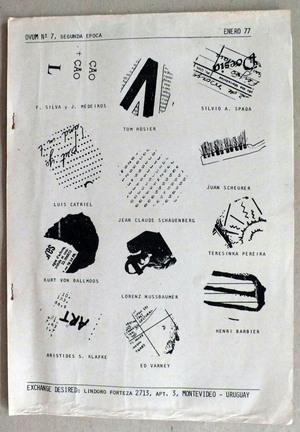

After 1980, mail art gained renovated vigour; in this period, we can highlight the following events: the inclusion of a session on mail art in the XVI São Paulo Biennale (1981-12-00 FBSP 001), in 1981; the creation of the Asociación Uruguaya de Artistas Postales, in 1983; the foundation of the Asociación Latinoamericana y del Caribe de Artistas Postales in Argentina. Furthermore, numerous exhibitions and alternative publications appeared, focusing on the diffusion of mail art: Diagonal Cero, Hexágono 70, Nuestro Libro Internacional de Sellos y Matasellos, Hoje, Hoja Hoy, in Argentina; La Pata de Palo and Margen, in Brazil; Post Arte and Marzo in Mexico; Ediciones Mimbre in Chile; and Ovum, Integración, Participación and 0 Dos in Uruguay.

Conclusions

The exchange of correspondence facilitates encounters between different people from different cultures who aim to share their specific problems. In this sense, communication brings solidarity to local events, creating a global network of solidarity that produces innumerable proposals related to the condemnation of daily problems. Hence, mail art assumes a broad reaching political position that encompasses issues that go beyond ideology, spanning ethnic issues, sexual options, the environment, wherein every image suggests social commentary. Consequently, we can conclude that the political-ideological nature of mail art is not exclusively limited to societies that live under dictatorial rule –notwithstanding its enormous significance in such societies– but extend to all societies.

Moreover, we must understand that although mail art asserts itself in the collective sphere through participation as promoted by the act of sending and receiving correspondence, it also configures itself as a political position. Seen in this light, its political stance is not necessarily located in its contents, but rather in its strategies and practices, the circulation and distribution of art. Indeed, the importance of mail art is not focused on the object (the correspondence), but on the process as a whole, which encompasses the circulation and contents of messages, as well as the relations of exchange between the emitter and the receiver.

Bibliography

Bruscky, Paulo (1985). Arte Correio. In: PECCININI, Daisy. ARTE novos meios/multimeios – Brasil 70/80. Exhibition catalogue. São Paulo: FAAP.

Freire, Cristina (1999). Poéticas do Processo: Arte Conceitual no Museu. São Paulo: Iluminuras.

Gache, Belén (2005). Arte correo: el correo como medio táctico. In: DELGADO, Fernando G. & ROMERO, Juan C. (orgs.). El arte correo en Argentina. Buenos Aires: Arte Correo Vórtice.

Stephanou, Alexandre Ayub (2001). Censura no Regime Militar e militarização das artes. Porto Alegre: EDIPUCRS.

Zanini, Walter (1985). A arte postal na busca de uma nova comunicação internacional. In: PECCININI, Daisy (org.). ARTE novos meios/multimeios – Brasil 70/80. Exhibition catalogue. São Paulo: FAAP.

LEÃO, Ricardo S. Entrevista a Clemente Padín. (On-line web). Available in: http://www.geocities.com/soho/lofts/1418/padin.htm. Consulted on: 22-02-2007.

YÉPIZ, Gerardo. Sobre Arte Postal. (On-line web). Available in: http://www.vorticeargentina.com.ar. Consulted on: 27-11-2001.