E.M.A.C. – The E’Net Mail Art Cloud:

Crackerjack Adventures With Formular Clouds

By Chuck Welch

The title E.M.A.C. is an acronym signifying E’Net Mail Art Cloud. The E’Net is a reference to Robert Filliou’s poetic vision of an Eternal Network. E.M.A.C. implies that a mysterious journey will shortly ensue and launch us towards a meandering account of simultaneous events. Sensation of light, energy and mass shall appear in an equation, a formular, a solution involving mail art archives floating in clouds. The E.M.A.C. is a mail art MAtrix cloud, forming and brain storming its way into the future, but first, may we indulge upon past events where identities merge and intersect, connections are established, and proposals propel us aloft?

An Eternal Triangle

Incensed and consumed by jealousy, he discovered the large stack of a stranger’s letters posted from Vietnam. The infuriated husband swore as each envelope, poem, drawing, correspondence and note was opened and hurled into flames. For months he secretly concealed the seething deed from his newly wed wife. Before this brief marriage ensued she had coveted the letters, guarded them closely, and hid them with the understanding that some day, her fine lettered friend might return to reclaim the art that helped him survive a wartime struggle with lost time, lost youth, and lost dreams.

I had sent these mailart letters to a girlfriend during my tour of duty in Cam Ranh Bay, Tan Son Nhut Air Base and Saigon Port from 1970-1971. At that time, I didn’t know that I was sending mail art, but the exchanges had all the trappings of that expressive form. Having graduated from college with an arts degree in 1970, I appeared before the draft board at the Kearney, Nebraska US Post Office, a shining edifice of early 20th century Greek Revival architecture that two decades later would become The Museum of Nebraska Art (MONA). I was drafted in this building, within the second floor main street office where today a work of art by an acclaimed American artist hangs on the hallway wall about twelve feet from the old draft office. The artwork is by my cousin, Roy DeForest, a famous Nebraska born artist who, with David Zack, Maija Peeples, Dave Gilhooly, Robert Arneson and Clayton Bailey launched the California Funk Art Movement, aka “Nut Art”. But in 1970, just weeks after graduating from college, I found myself in the empty and drafty hallway. I caught the draft and in four months I had orders to serve in Vietnam.

Mailing Art From A Warzone

After Basic Training at Ft. Leonard Wood, Missouri I tried to make the best of a bleak situation. While briefly serving at Fort Eustis in Virginia, I applied and qualified for a position in the U.S. Army Combat Art Program. This entailed visiting firebases, drawing equipment, and going on sporadic patrols for a brief period of three months and then developing the artwork for nine months of temporary duty in Hawaii. Unfortunately, the program was discontinued before I left the States. Instead, the art I created in Vietnam found its way inside scores of letters to my girlfriend back home; envelopes stuffed with drawings of Charlie as he was captured and sent for interrogation. I mailed letters containing photos of the bombed out headquarters of my unit, poems about barbed wire, perimeters, portrait drawings of friends, recollections of guard duty and my first encounter with an exploding 120-millimeter incoming mortar round. All these visual artworks, poetry, and handwritten recollections were burned, wasted, consumed by someone’s fit of rage. Like my letters, I was burned out as I returned home to Nebraska from Nam in time to share Christmas Eve, 1971 with my parents, brothers and sisters.

Omaha Flow Systems: The Internet’s Skivvies

Ever since my Army tour of duty, I’ve always associated mail call as an art calling; a communication lifeline, a vital link connecting me with the world. Mail art has been an escape from the isolation of many kinds; emotional, geographic, cultural, and institutional, so it was not surprising that I would stumble across Omaha Flow Systems (OFS), a very important historical mail art event that occurred in Omaha, Nebraska during the Spring of 1973. I found thousands of artifacts, objects, correspondences, postcards, stamps and letters posted not only in Joslyn Art Museum, but also in Omaha’s shopping malls, in corporations and churches, in educational centers such as Creighton University and The University of Nebraska. Reports were printed in the Omaha newspapers, and broadcast over local and regional radio and TV. Mail art at Omaha Flow Systems was a mass media technological event for that era. In short/s, OFS was the proto-internet, the internet’s skivvies. The project has often been overlooked as the central grounding space where Fluxus and correspondence art merged together as a public form of mail art networking.

The OFS flux that fused together art and networks was applied by co-curator, Ken Friedman, the youngest member of George Maciunas’ Fluxus Art Movement. My interactive experience with OFS introduced me to more than mailing art...here was artwork from around the world networked as public art finding its way into the everyday lives of the citizens of Omaha, Nebraska. What seemed most remarkable to me was that “non-artists” were allowed to take artwork off the walls of Joslyn Art Museum and replace it with their own creations. There were some notable artists who swapped “free art” with the public; artists like Robert Indiana, Fluxus sculptor Alice Hutchins, Ray Johnson’s postcard pal, May Wilson, and David Zack, a co-founder and poet of the California based Nut Art movement who stopped by Omaha to see the exhibition on a sojourn from New York City via Kansas City to Silton, Saskatchewan, Canada.

A Mail Art Launch from Ground Zero

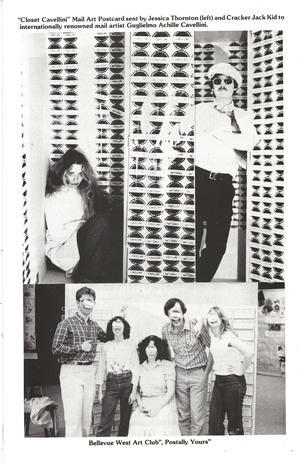

Not long after seeing OFS, I embarked on my first teaching job in Bellevue, Nebraska. Beautiful Bellevue was an Omaha suburb just a mile from The Strategic Air Command, a cold war nuclear target often known in America as Ground Zero. What an unusual place to discover the avant-garde through mail art networking. What an appropriate place to introduce anti-war mail art projects, peace stamps, and organize three national high school postal art exhibitions, all launched from my high school art classes brimming with teenagers whose parents worked at nearby Offut Air Force Base, home of the Strategic Air Command. The third high school mail art exhibition was international and included a network of 76 high schools. I received a Hilda Maehling Fellowship from the National Education Association and exhibited the show at their headquarters lobby in Washington D.C.

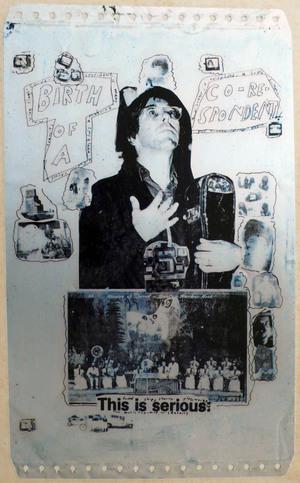

Crackerjack-Zack, and Modern Mail Art

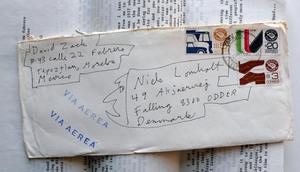

Weaving together networks by using the mail or internet is often an imprecise, random activity filled with surprises. The aleatory chance of unplanned encounters was like pulling a free surprise out of a crackerjack box. Mail art in a crackerjack mail box became my metaphor. This explains my playful mail art nom de plume, CrackerJack Kid. I recalled taking my first piece of mail art off the walls of Joslyn Art Museum in April 1973 and thinking of the work as a free prize that I could take home. By chance, a few years later, I was surprised to have a letter from David Zack, California Nut Art poet, who informed me that he too was at Omaha Flow Systems. Zack wrote that Omaha Flow Systems was “a computer concept.”

Between 1982-1994 I would be exchanging over 100 lengthy correspondences with Zack, an eccentric mentor who, unbeknownst to me, was a close friend of my famous cousin Roy DeForest. Through these correspondences, Zack would inform me that he and Roy were co-collaborators in the founding of the California Funk Art Movement, otherwise known as “Nut Art”. Zack made the observation that “nuts” were also found in crackerjack boxes along with the carmel corn candy and free surprise.

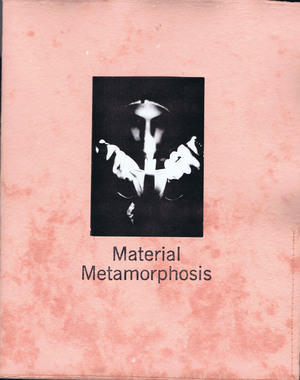

My first correspondence art encounter with David Zack occurred July 22, 1982 when he sent a seven page letter praising me for an important contribution to the evolution of formular publishing. At that time I had no idea of what Zack meant by “formular publishing”, but he stressed that Material Metamorphosis was also one of the most elegant contributions to the Commonpress series started in 1977 by Polish book artist and mail artist Pawel Petasz. I didn’t know that Zack had been using the documentation from Material Metamorphosis as a contact list as he was writing a book about mail artists in a manuscript titled Modern Mail Art.

By March 21, 1982 Zack had already completed 126 pages of Modern Mail Art; a book that was to be 250 pages with thirty illustrations. Among the twenty five chapters listed in his manuscript outline, fifteen have been accounted for. David Zack mailed three manuscripts to three recipients; CrackerJack Kid, John P. Jacob, and Salt Lick Press. In two years of research I was able to locate three additional chapters. John P. Jacob, couldn’t recall if he’d received Zack’s manuscript, but wrote that he’d destroyed his own archive years ago. The editor of Salt Lick Press died in 2005 and left no records, so I had reached a dead end with all this detective work. We may never find Chapter 19, “Chaw Mank, Musicmaster & the Krono-nuts” and learn what it is that the three have in common which Zack felt was so extraordinary. But we are lucky to have a copy of Chapter 7 entitled "What’s A Formular?” where Zack reveals Lomholt’s risque “formular performance” in Australia.

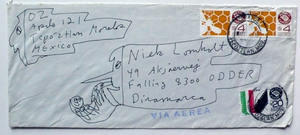

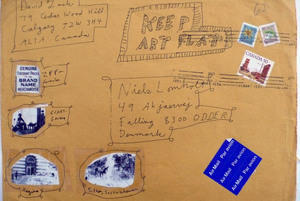

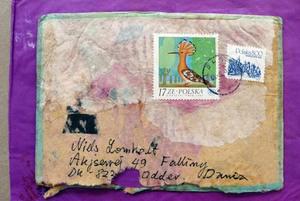

Apparently, I was the only one of three who had half of the twenty-five chapters appearing on the outline. Thanks to the incredible archival preservation work by Niels Lomholt, I discovered to my joy, that he too had received Zack’s outline with half of the chapters listed. Lomholt had four chapters of Modern Mail Art that I didn’t have. Altogether, with Niels‘ help I have 136 pages of Modern Mail Art which I intend on publishing in the next year. Most recently, after pouring through my archive and pulling out hundreds of Zack’s letters, all densely written, I discovered a brief passage in which Zack confided (June 1984) that he had written 136 pages before abandoning the project for another equally elusive endeavor titled Correspondense Novels.

Common Pursuits and Commonpress

Niels Lomholt and I have much in common. Besides corresponding with some of the same mail art friends like David Zack, Al Ackerman, and Lon Spiegelman, we also had professional jobs as high school art instructors and as such, we both introduced our students to mail art in the classroom. There are also the presence of mutual friends in our archives, work that reflects our shared interests in artists’ books and zines, particularly a famous assemblage publication known as Commonpress. The mastermind behind this title was Polish mail artist Pawel Petasz and I had the privilege of collaborating with him in editing Commonpress issue No 47: Material Metamorphosis.

Commonpress was unique in how each issue had a new editor devoted to diverse themes. My issue, No 47, was a mail art project merging handmade paper and mail art. Throughout 1982, I pulped 25 lbs. of cotton clothing with a laboratory beater in my basement handmade paper mill. My address in South Omaha became the collecting point for the mailed material remnants of rags worn by 130 mail artists from 16 countries. The process was a kind of magical transition of mail artists’ favorite clothing transformed into handmade paper stationery. The paper moulds I used to form sheets included my hand stitched watermark of a dove rocketing out of a postal cancellation mark. I had been crafting boxed handmade paper for The Smithsonian Institution and New York City Central Supply Company, so I had many dark brown stationery boxes available to use for the Material Metamorphosis project. The handmade paper mail art clothing rags became beautiful lavender envelopes and note paper that I delivered to all the participants with one additional request; mail one sheet and envelope as a statement of “self-identity”. Exquisite artworks were returned by Buster Cleveland, Bern Porter, Robin Crozier, Richard Kostelanetz, Edgardo Vigo, Ray Johnson and many other mail art pioneers. These works were then exhibited in an exhibition at Bellevue College, Bellevue, Nebraska (1983) and at the San Francisco Art Institute (1984).

One of the most interesting deliveries of clothing to the Material Metamorphosis project was by Ray Johnson, the father of mail art. Ray declared that he fished his old webbed underwear out of the bottom of his garbage can. Once retrieved, he sent everything but the crotch which he declared had food stains on it. Thereafter, Ray and I began corresponding and telephoning on a regular basis until he died in 1995. I had the pleasure of meeting Ray on three occasions, the first being a personal invitation to rendezvous with him at the Nassau County Museum of Fine Art for a private tour of his first and only retrospective exhibition. Ray Johnson and Cracker Jack Kid performing "Nothing" in February 1984 at Ray's Nassau County Museum of Art, Roslyn Harbor, Long Island.

Commonpress is legendary for having established the ultimate expression of democratization in book art and periodicals. As Petasz was constantly hassled and censored by communist agents, he managed to create a global periodical of floating editor/partnership that was open to all contributors who became part of a network from which future editors were chosen. My collaboration with Petasz introduced him to hand papermaking. From my basement handmade paper mill in Omaha, I created a mould and deckle for Petasz, stuffed cotton linters in a package and mailed it with instructions to his address in Poland. By some miracle it arrived unscathed, and within weeks Petasz was mailing amazing handmade paper envelopes to Zack, Lomholt and I.

The Formular and Formular Publishing

David Zack was also a close friend of Niels Lomholt, famed Danish photographer, video and installation artist who pioneered the concept of “formular” mail art activities. Both Zack & Lomholt were corresponding in the early 1970s, meeting each other in 1978 at Egmont, Denmark where they collaborated in “Celebrite-79", a project with Lomholt’s high school students. At the time of Omaha Flow Systems, Zack, who was a reviewer for Art Forum, had written a landmark mail art story that appeared on the cover and pages of ART IN AMERICA. In 1972, Zack became interested in the idea of “formulars” through correspondences with Niels Lomholt, and by 1978, Zack was expanding upon Lomholt’s concept with the creation of “formular publications”. Many of these activities can be found in Zack’s 1982 publication titled “Report on Formular Activities: 1973-1982”. It was the formular connection with Lomholt that sparked Zack’s imagination and later resulted in the creation of the Modern Mail Art manuscript (1982-1984) and Correspondence Novels (CNs), (1984-1987); two of Zack’s most notable contributions to the history of correspondence art. Lomholt’s “formular” became the trigger and spark Zack used to launch correspondence art into an experimental networking orbit beyond Ray Johnson’s influential “New York Correspondence School”.

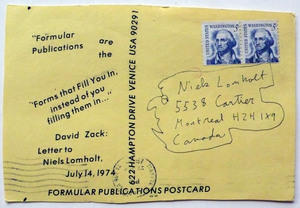

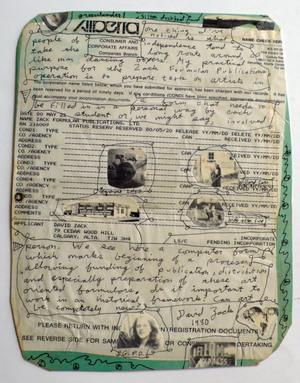

So what is Niels Lomholt’s formular and how does it apply to publishing? A “formular” is something that needs to be filled out. We all fill out forms, they are bureaucratic tics that stick, prod and infect our lives with all forms of intrusive information designed to compromise one’s money and privacy. But the kind of form that Niels Lomholt provided came without instructions. Recipients, instead, are left to fill in blank lines with texts and visuals that denote any kind of meaning. Formular “content” is teased and cajoled with lines requiring texts and empty squares sometimes labelled as “fig.” Lomholt’s formular “squares” remain open to more than a figurative check, or x marks the spot. Zack’s “Formular Publications”, for example, made correspondence postcards, letters and envelopes the canvasses for formulars as defined on a postcard to Lomholt dated July 14, 1974, “Formular Publications are the forms that fill you in, instead of you filling them in”. In 1980, Zack applied the idea to computer forms and to “formular blanks”; empty spaces on the back of envelopes, margins and columns of letters.

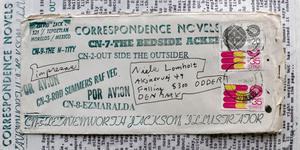

From 1984-1987 Zack linked his concept of formular publishing to “correspondence novels” (CNs). Each novel included ten chapters and a correspondence cast of fourteen artists; Al Ackerman, Rod Summers, Leavenworth Jackson, Istvan Kantor, Niels Lomholt and I among many others. My plot appeared in CN*5: Leavenworth Jackson Illustrator. Zack tried on numerous occasions to orchestrate a connection between me and my reclusive cousin Roy DeForest, founder of Nut Art and the magical painter of mystical dogs. My middle name is DeForest, but for whatever reason, Roy, my grandfather’s nephew, abandoned his Nebraska roots in 1937, leaving the Dustbowl for California. Roy, wiping away the memory of his father’s bankrupt family farmstead, was reticent about acknowledging the past or maintaining contact with relatives from Nebraska. In retrospect, I discovered it was Zack’s past association with Roy that caused my cousin’s reluctance to communicate.

Zack, the romanticist, imagined ways to bring love and intrigue into his correspondence novel chapters. He tried to arrange some real crackpot “situations” between “Panman” Mark Block & a painter named Izmarelda. In another chapter, Zack tried to play matchmaker between the happily married Russell Butler living in Gurdon, Arkansas and a renowned California rubberstamp artist and illustrator, Leavenworth Jackson. Some of the results were hilarious accounts of Zack’s backfired role as matchmaker.

Unfortunately, like so many of Zack’s projects, publication of his correspondence novels floundered although the book could be reassembled today through a diligent networking effort to reconnect the aging characters in his novel. Indeed, it was Zack’s original belief that each of his ten chapter novels could best be assembled by posting them on a computer where all of the 140 participants would be able to access the info online digitally. What if David Zack had lived long enough to include Twitter and mail art chat rooms for his novel approach at formular publishing? Would the result be as interesting and entertaining as they were in the twilight of late 20th century letter writing?

The importance of “electronic mail” was acknowledged very early by Zack and he saw it’s advantage in the dispersal of what he coined as “correspondence art”. On July 22, 1983, Zack wrote to me, “When it comes to correspondence and publication all my thoughts are on doing it electronically, a la Telidon as it’s developing in Canada. The reason is simple. As long as we work with paper, no matter how beautiful, there’s a basic cost which pressures for editing, for economy. My feeling is that in correspondence everything is relevant and even important, and that unless it’s easily available it might as well be lost.”

Zack knew about modem to modem communication by phone in 1983 based on a 1980 visit to the Telidon installation in Calgary where he talked with the supervisors of the project at Alberta Telephones in Edmonton. He left that meeting with the belief that “communication between any two or more entities on that network will most probably (make it) available to everyone living in Canada before the end of this century (Letter to CJ Kid dtd. July 22, 1983). In a letter to Niels Lomholt dated July 19, 1982, Zack prophesied how formular publishing would merge into electronic publishing, “...the real way to do it is with computer files that handle photos and other graphics and can shape the words in any style you want, as large or small as you want and using visual as well as literary language. More than likely translation could be taken care of directly, so if you wanted to put some English material into Danish You’d simply as your machine with the flip of a key and it would do it.”

Lost Archives: How Mail Art Dies

What becomes of mail art archives with the passage of time? What happens to thousands of work exchanged with others? Some mail art is lost, thrown out by the relatives of deceased correspondence artists. Some mail art is sold to art dealers and can be found today on the internet with a price tag. Some work is destroyed intentionally by neo-dadaists, or in conceptual performances. A portion of mail artwork is altered by other artists as an add-on, sometimes it’s tossed away carelessly or intentionally. Fire, flood, rain and snow vanquish mail. Only the postal gods know how much mail art has been lost by mail carriers, stolen, damaged by sorting machines, confiscated by postal censors, lost to dead letter offices, or ripped to shreds by dogs hounding hapless mail carriers on their delivery routes.

I’m certain that in the future a large quantity of my mailed art to others will be sent to dumpsters by the relatives of deceased mail artists. But a sizable portion of my mail art work had the good fortune of being placed in private art collections and archives that were carefully preserved. Jean Brown, an ardent supporter of my writing projects, NETWORKING CURRENTS (1985) and ETERNAL NETWORK MAIL ART ANTHOLOGY (1995), sent her entire collection of mail art, including my own correspondence with her, to the Getty Museum in Malibu, California. Librarian and mail artist, John Held Jr. donated over 600 titles of mail art zines to The Museum of Modern Art in New York City. As a consequence, all of my issues of NETSHAKER (1993-1996) and NETSHAKER ONLINE, mail art’s first ezine, (1994-1996) can be found in MOMA’s Library. Held also included over 50 of my correspondences about mail art and networking in the Smithsonian Institution Archives of American Art, Washington, DC. My Networker Databank was mail art’s first archival project on the internet. It was created during the Decentralized World Wide Mail Art Congresses, 1992, and is housed today at the Museum of Modern Art, NYC Library Collection and The University of Iowa Alternative Traditions in the Contemporary Arts Archive, in Iowa City, Iowa.

An uncertainty arises whether these mail art archives and collections be used as tools for mail art research. The question is a debatable one, especially when it is a fact that there is no standard digital map for locating or categorizing mail art ephemera. I can hear a distant echo emanating from Denmark that grows louder with every line I write. Niels Lomholt is pacing impatiently in the wings ready to take off and fly to the clouds. If I am to launch E.M.A.C. from this paper draft and touch the cloud, I must quickly join the past with present tense. Well, a “present” in the instance of mail art, is also a gift and the gift that Niels has proposed is a gift that will keep on giving. That’s quite a formular for success.

The 2010 publication of Lomholt Mail Art Archive, Fotowerke, and Video Works was evidence that at least one at least one prominent mail artist from the 70s had achieved success with a book documenting the existence of early mail artifacts. Lomholt’s book also led my search in his direction for locating six lost manuscripts belonging to David Zack. Most recently, Niels sent an invitation to contribute a text as a “Mail Art Old Timer”. How that text will ultimately be launched is still a mystery, but there are hints Niels will link it to a “cloud performance” sometime during 2014.

I’ve discussed earlier how Niels Lomholt defines “formular” as a situation, or condition of something, or a common language. A formular, I would venture to conclude, is definitely more than a piece of paper, it is a piece of cloud. Lomholt wants to place his archive in a digital form that welcomes interaction. Lomholt realizes, as I do, that something must be done with all the stored, archival information. The formulae to cloud formation requires new archival forms to fill out and add to the collection. The process is open and transformative as it is informative.

Back to the Future

Cloud computing relies on sharing resources, but most archival clouds are formed as a business model. It’s doubtful that a pay-per-use basis is Lomholt’s formular. In the most general sense cloud computing as a mail art formular will be a website managed by a mail artist or art institution. In late 1994, I created The Electronic Museum of Mail Art (EMMA) at the Dartmouth College Kiewit Computation Center where EMMA became mail art’s first webpage. My proposal has been sent to several universities to update EMMA’s website with new web technology using dynamic PHP & My Sequel access. As in 1994, there will be no fee for entry, no museum guards, or membership access cards. Visitors may choose to freely navigate through the library and acquire information from the Eternal Network Mail Art Archive Database. There will still be EMMA’s exhibition rooms, plus some additional new spaces.

The body of my Eternal Network Mail Art Archive encompasses texts, catalogues, and two dimensional artworks that are categorized and filed by postcards, posters, envelope art, artists’ books, artistamps, collage, copier art, rubberstamps, sticker/tickets/tags, visual poetry, correspondences, media news and articles, mail art exhibitions catalogues, mail art projects, zines, audio art, T-shirts, and small, 3-D mail artworks. Like Lomholt, I have an enormous collection of these materials that fill over 70 filing boxes. Recently, I completed a half year task of cataloging my Eternal Network Mail Art Library that includes 1008 mail art books, artists’ books, posters, mail art projects, documents, and exhibition catalogs. I was impressed when Niels wrote to say he had archived over half of his collection in a couple of years. It has taken me nearly twice as long to do as much work on my archival database. Ten thousand scans of materials resulted in wearing out two HP Officejet machines. I have managed to digitize about half of my archive in a framework program. My ultimate objective is to create an interactive archive that includes an innovative, digital, matrix menu.

I agree with Niels Lomholt that “it would be a waste, and heartbreaking to let it (Lomholt Mail Art Archive) pass to mother earth.” The complexity of categorizing mail art ephemera is an acknowledged challenge for the library sciences. Most often, it has been individual mail artists like Keith Bucholz, John Held, Jr., Mogens Otto Nielsen, Niels Lomholt, Lutz Wohlrab, Ruud Janssen, Guy Bleus, Geza Perneczky, Julia and Gyorgy Galantai, and others who have structured their archives and made them accessible over the internet. We are only a handful of aging artists who lack the support of mainstream libraries, and art institutions.

In the summer of 2011, I attended the Bern Porter Symposium at Colby College in Waterville, Maine where I had the pleasure of hearing a symposium lecture about Bern Porter that was delivered by publisher/poet, Mark Melnicove. The lecture revealed important information about Bern Porter’s archive of mail art and found poetry. Porter, who I eventually met in 1982 at his home in Belfast, Maine, spent most of his last years diligently archiving an enormous collection of mail art and found poetry. Bern Porter’s life was a remarkable journey that included his youthful interaction with Gertrude Stein. He was also a research scientist who contributed to the Manhattan Project during World War II. Bern’s mail art obsession for archiving found objects and found poetry is a remarkable story in itself. Through the years he painstakingly catalogued all of his poetry and mail art according to specific criteria that were relevant to his aesthetic sensibilities. All of his found objects were transformed into a database foundation for future studies that resulted in the creation of eleven major archives for eleven institutions including The Getty Museum, Brown University and Colby College.

The Bern Porter symposium lecture delivered by Mark Melnicove left me with an indelible impression. My Eternal Network Mail Art Archive was left dormant for a decade before I approached it in 2009. At that point my interest in mail art networking was revived and took on a different tack. Most of my predictions for mail art and network art implementing the internet as a major source were validated in my Telenetlink Internet Project (1990-1996). My re-discovery of mail art was as much about the form finding me, as I was of finding "it". In short, my archive became a "re-found object" and inspiration for renewed life, fresh ideas, excitement and newfound enthusiasm. Between the lines of Melnicove's lecture, I wrote the following note in the symposium program of events; a recognition that my mail art archive had found me, "I’ve become the object of my archive; a found object." This archival work continues today and now I am creating new mail art friendship and exchanges with projects involving handmade paper, collage, and a fascinating exchange of information and ideas with Niels Lomholt.

I look forward to seeing the Lomholt Mail Art Archive emerge as “a cloud solution”. Barring any mysterious events that send the world quickly back to a technologically pre-industrial age, Lomholt and CrackerJack’s clouds won’t sprout mushrooms, but will resemble a net formular in which a net is a functional fabric, not a fabrication of function. How Niels propels us all into the cloud is an event worth marking on the new Mayan calendar...hopefully, a formular without archival virgins sacrificed and thrown into wells or volcanoes.