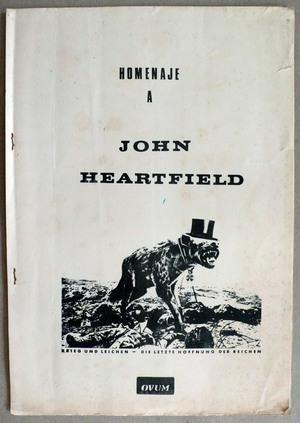

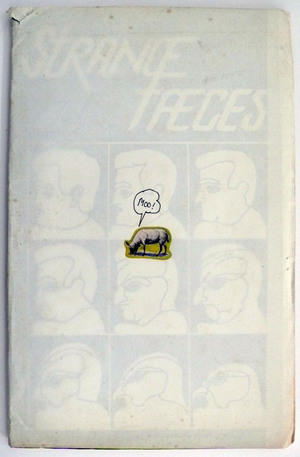

FOCUS V | Global Network Zines:

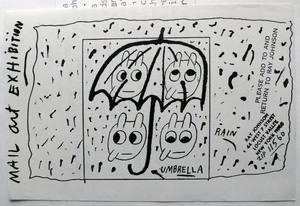

The Public Face of Mail Art 1970-1985

By Chuck Welch.

“Thanks, but I think I’ll pass on the mainstream tonight, dear”.

Before Pinterest, Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter, mail art publications were passageways where papernets met internet, typewriters went electric, copiers found color, printers morphed as lasers. Fax, PCs and MACs went telematic. Music tapes, 8-tracks, and vinyl recordings became “retro” in the fast forward age from analog to digital. In the information age, art trends had shelf lives that flourished, flashed, imploded and exploded. Art bounced from Pop to Punk and California Funk. It leaped from Fluxus to Correspondence Art to Neo Dada and Mail Art. Meta-nets met telenets. Netlinks found the internet as art was webbed world wide. By the millennium, mail art and everyone else had moved far beyond the yellow brick Rolodex road.

The public face of mail art constantly evolved during the years of 1970-1985. The largest collective history that emerged from those years were logged in zines published by independent, contrarian artists. When the dust had settled mail art had not “excused itself from history” as Village Voice columnist, Greil Marcus proclaimed in 1984. Instead, mail art personified a “living history”. The late David Cole, a famous vispo artist and mail art philosopher with a doctorate from Princeton, said it best, “Mail-art is the literature and art of our time. It is a diary - honest, sincere, and beautiful”. 1

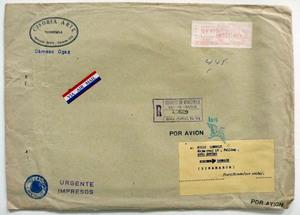

Most mail art zines, catalogs, and projects were part of the underground culture during the 70s and early 80s and were passed unknown through mailing zones, sorted, postmarked, distributed, and sometimes confiscated by postal authorities. Some zines were obscure and private, but hardly discreet. By any standards, mail art zines, from poetry to porn, were seldom cloaked in brown wrapping. Invariably, North American zinesters desired public exposure with production runs that would land on newstands. That was the utopian, public ideal many zines aspired towards. Occasionally, it happened, as did FILE from 1972-1989. FILE was a famous post-fluxus magazine from Canada that quickly gained a reputation far beyond it’s Toronto underground roots. Published in production runs of several thousand copies, FILE was a spoof on LIFE Magazine and exerted an enormous influence upon neo-dada and mail art.

Any way you spelled it out, a zine, pronounced ZEEN (short for fanzine) would never make one rich. A publishing income was more of an outcome. Zines were zilch for milking wealth. The mail art zine world, circa 70s, was a small-fry, self-publishing endeavor pursued mostly by individuals as mail art catalogs, project documentations, or self published magazines.The norm for a zine edition was most often fewer than 100 copies and rarely more than a 1,000 copies. Luck was in breaking even; much better to trade, gift and barter ideas. For most zinesters, breaking the rules of traditional publishing and challenging authority was enticement enough. Furthermore, the advent of quick copy publishing made it possible for everyone to create on a level playing field. Mail art fanzines were collectible and quickly became a prize in every mailbox.

Mail art had both public and private sides. Mail art zines and other ephemeral postal artifacts from postcards to copier art appeared in public exhibitions; on the streets, in bathrooms, bars, apartments, post offices, shopping malls, town halls, alternative galleries, art museums, hospitals, libraries, high schools, colleges, and universities. Mail artist John Held, Jr. wrote in his sourcebook, International Artists Cooperation: Mail Art Shows, 1970-1985, that mail art shows grew in size from five in 1971 to seventy-five in 1979. “By 1984, this number had exploded to one hundred and eighty-seven”. 2 By the late 80s over a hundred public exhibitions of international mail art were occurring every month. Inevitably, some curators and institutions took advantage of the artists’ gifts. Making that observation, Los Angeles mail artist and publisher, Lon Spiegelman, advocated in 1980 that mail art exhibitions honor a set of guidelines: All work shown, no fees, no jury, and free documentation to all participants. These simple yet highly effective mail art guidelines remain today.

Ray Johnson and His School of CorresponDance Art

In the late 1940s, long before correspondence art and public mail art shows existed, a young artist from Detroit, Michigan named Ray Johnson studied under Joseph Albers at The Black Mountain College near Ashville, North Carolina. Johnson started creating moticos in the 50s and soon after began sending pieces of mail that directed his recipient to “add-on to and return”. Johnson began invading mailboxes everywhere with bunny heads, correspondence wordplay, imaginary “fan clubs” and gatherings arranged with complete strangers. Ray Johnson was a friend of Joseph Cornell, Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenburg, Chuck Close and many other famous artists, but until his death in 1995, Johnson was seen as a reclusive, eccentric artist whom art dealers found difficult to promote. No wonder Ray Johnson was named by New York Times art critic Grace Glueck, as “New York’s most famous unknown artist.” Ray Johnson’s collage of Elvis Presley #1 (ca. 1956-57) made him Pop Art’s pioneer and indeed, the late Warhol was quoted as saying he’d pay ten dollars for anything by Johnson. 3

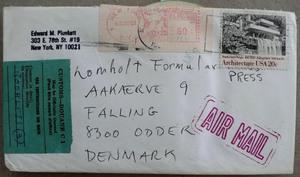

Johnson’s association with Fluxus artists in the early 60s is tenuous and while he performed once in 1961 with the New York City Fluxus artists and was published by Fluxus artist Dick Higgins, Johnson remained aloof. In a 1994 telephone conversation with CrackerJack Kid 4, Ray Johnson bluntly declared his viewpoint about Fluxus, “I’m not Fluxus, Cracker! I’m the New York Correspondance School!” In “An Interview with Ray Johnson” by Henry Martin, Johnson remarked, “I myself, in fact, never called it (New York Correspondence School) a “school” or talked about “mail art”. 5 The “school” referenced by Johnson was named by NYC collage artist Ed Plunkett in a letter addressed to Johnson. The activity that most adequately describes Ray Johnson’s mailing activities is known as “correspondence art,” an intimate, personalized, creative, and less public form of mail exchange as compared to “mail art.”

Ray Johnson’s “correspondence art” appeared in the early 60s, as The New York Correspondence School of Art, a satire of the well-known New York School of Abstract Expressionists in which Johnson chose his pARTners by virtue of his position as leader of the corresponDANCE. Many of Ray Johnson’s hub of friends included renowned artists like John Cage, and individuals like Elsa Maxwell and James Barr from the Museum of Modern Art. Johnson’s earliest collages and mail exchanges, before “killing” the school in a 1973 New York Times obituary, were estimated to be 200; by today’s Facebook standards, a miniscule fanclub, at best.

Ray Johnson’s influence, however, cannot be calculated or measured by mere numbers. The Hungarian underground magazine network authority, Géza Perneczky points out that the size of Johnson’s “school” was important in the way it “functioned”. As such, the question arguably remains whether The New York Correspondence School of Art amounted to a “network” as much as a “list”. 6 Indeed, Johnson disliked “networking”, “network” and “mail art” as descriptions of his mail exchanges with others. As the core figure of a “school”, Johnson explained his activity “as a writing activity” and to those seeking to find out about his school he advised, “The only way to understand it is through participation, because what I do is made for each person.” Johnson continued, “My strange personality determines the whole activity of the Correspondence or dance School.” 7

Ray Johnson was a creative, witty wordsmith although it can’t be determined if he understood or cared that an open network, or “art that networks” isn’t centralized or controlled by the orchestrations of a single individual. Ray’s “school” was not a network and to call it such is an oxymoron. Ray poked fun at the 1992 networking year as “nut-working” and chose not to participate in hundreds of international activities. Johnson also failed to collaborate in the 1986 mail art congress year. Instead, Ray Johnson enjoyed a home based kind of organizational authority where his Rolodex-like “school” was managed by countless lists, cleverly drawn and played out through the privacy of the mail. Ray was clearly a “not-worker”. Perhaps “network” was his expression for “nothings” or a disagreement with terminology (networking) that implied work rather than play.

In 1970, Johnson’s private school came to the attention of Marcia Tucker, the Whitney Museum’s curator and she extended an invitation to Ray to co-curate a New York Correspondence School Show. 8 When Tucker thought Johnson’s Whitney show should be educational, Johnson remarked years later, “She (Marcia Tucker) thought it should be educational. I thought nothing should be seen. I looked at it all in the basement. What did I care about the city of New York and the pubic? Marcia Tucker said, ‘People should be able to see it. It’s a public museum.’ I don’t agree.” 9

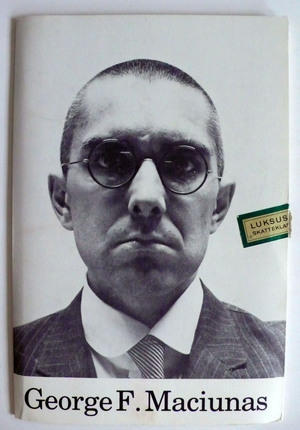

Fluxus, Maciunas & Mailing Strategies

Around the year 1958, sensibilities of everyday life merged with artistic life until the traditional artistic disciplines were either boxed and broken down into mass-produced art, or performed in alternative spaces. The Lithuanian born “founder of Fluxus” (Latin root -”to flow”), and architect, George Maciunas (1931-1978) was first to close the gap between art and life. This paradox of closing gaps was also performed with humor, spontaneity, chance, and the breaking of barriers. According to concrete poet and Fluxus artist Emmett Williams, Fluxus was above all “a form of open-ness: open-ness, you might say, practically to the point of dissolution.” 10 At this early date one can trace an “open” continuum, a fluxus tendency that largely influenced mail art publications and the guidelines for exhibiting mail art in public institutions.

Fluxus, from the beginning, was a collective endeavor among artists who felt dismissed from the centralized distribution system of the art world. Their egalitarian, non-professional and non-elite status was aimed at seizing production’s medium and demonstrating that anybody could produce art, music and literature. This do-it-yourself aesthetic shared some common ground with mail art’s public, decentralized network presence. Unlike Ray Johnson’s private, correspondence activities among friends and “chosen” contacts, Fluxus began, in part, with George Maciunas’ intention to create “multiple” kits, collectibles, games and ideas for public distribution and sale.

Mail was central to the international distribution of Fluxus objects through Maciunas’ Flux Mail-Order Catalogue and Warehouse. While Fluxus artists were the first to grasp the importance of using global mail systems for the distribution of Flux objects, it was not a determined way to engage public dialogue. Fluxus artist Ken Friedman observed, “In the 1960s, Fluxus was years away from its eventual pubic impact. Even though publicity was implicit in many Fluxus projects and activities, the activities were not yet fully public”. 11 By the late 60s some Fluxus artists began using correspondence art as a private medium among themselves, but not as a public “mail art” dialogue. At best, the 1960s Flux Mail-Order Catalogue and Warehouse used the postal system as a marketing clearing house for product distribution. Ironically, Maciunas’ efforts cost him more to produce than he profited. Clearly, not all Fluxus products were intended for a network devoted entirely to free exchange as found in the global mail art network.

B.A.D. - Mail Art’s Neo Dadas & Mamas

During the early 1970s, the San Francisco Bay Area Dadaists, also known as B.A.D. were actually good. In fact, they were really excellent, and like their forebears, the Swiss and German dadaists, the B.A.D.s excelled in pranks, performances, publications, public gatherings, events, poetry, and anti-art, all against the backdrop of cultural upheaval and the Vietnam War. Both camps were absurd, provocative, banal, and anti-aesthetic in the most irreverent context, and that too, was very good. While the world was their performance stage, the world of high art, as usual, rarely attended. Monte Cazazza, a leading Bay Area Dada performance artist and one of B.A.D.’s greatest pranksters, was asked for a telephone interview in 1979 and commented, “No, No, No!” he said, “I don’t need to talk, I don’t need to make quotes. You see, I’m already very widely unknown.” 12

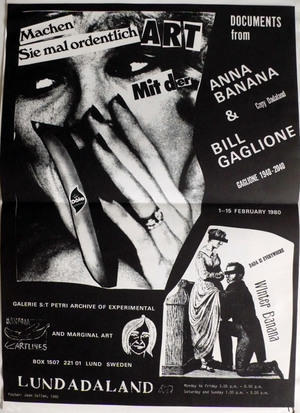

Today, a Linkedin internet search reveals there are sixteen individual Dadas from the San Francisco Bay Area with names ranging from Uzair Dada, CEO of Iron Horse Interactive to YourFather DaDa, “the main guy at educating Yall”. But in 1975, in a mail art postcard photograph labelled “Bay Area Dadaists: Ineffectual Student Art Groupies” there are Ken Doll, Joel Rossman, Bill Gaglione, Carlo Cicatelli, Tim Mancusi, Indian Ralph (Mancusi’s brother), Opal Nations, (and Jorge Zontal. 13 Two of the three leading influential B.A.D.s, Tim Mancusi and Bill Gaglione minus Charles Chickadel, are present in the photo and are contributors to the history of mail art dadazines. Some other B.A.D. artists who created zines and public mail art exhibitions, but were not in the postcard are Anna Banana of Banana Olympics fame, the late Patricia Tavenner a.k.a. “Mail Queen”, Ginny Lloyd, organizer of Inter-Dada 84, and Robert Rockola, a rubberstamp master, who, with Buster Cleveland, co-edited a “rebirthed” 1980 edition of The NYSC Weekly Breeder.

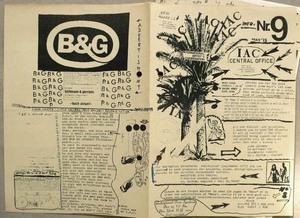

The Bay Area Dadaists were a magnet for collecting, generating, and dispersing information about rubberstamps, mail art, performance art, and especially publications focused on debunking and parodying mass media. Fluxus West artist Ken Friedman, the original editor of New York Correspondence School Weekly Breeder, created ten issues as a way to establish a regular, weekly contact list with other artists. The editorship was passed on to a long-standing friend of Ray Johnson, Stu Horn who later passed the periodical to Bill Gaglione and his cousin Tim Mancusi. Gaglione also published Dadazine, Charles Chickadel edited Quoz and The West Bay Dadaist, Pat Tavenner published Mail Order Art, Anna Banana launched Banana Rag and later on, VILE, a title caricature of LIFE. These publications influenced the zine culture, artists’ books, punk rock, and the creation of an international mail art network.

Bill Gaglioni, a.k.a. “Dadaland” (Bill Gaglione & Buster Cleveland) and “Grand-DaDa of the rubber stamping world” pioneered many contributions to mail art, copier art, visual poetry, sound poetry, zines, and rubberstamps. In the 1970s he founded a rubberstamp company, Stamp Francisco, and also created the Stamp Art Gallery, a space where he publicly exhibited and curated mail art, rubberstamps, and artistamp exhibitions. Gaglione and his cousin, Tim Mancusi, made first reference to dada artists activities as “the Bay Area Dadaists” (a.k.a. B.A.D.) in the May 1972 issue of The Weekly Breeder. Tim Mancusi and Steve Caravello provided collages for the covers of the “Breeder” while Bill Gaglione provided many pages of content with visual poetry, collage and innovative type and lettering designs. Mancusi’s Max Ernst-type collages and underground cartoon style often lampooned politics and religion.

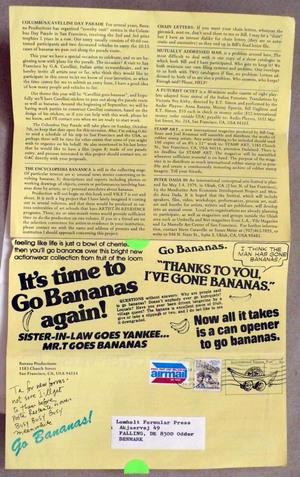

A publication of MIT Press lists Banana in its index as Anna Freud. 14 Whether Freud or not, Anna legally changed her name, forever A. Banana, a pseudonym that originated in 1968 during her five year elementary teaching stint at Vancouver’s New School. In Victoria, Banana played “The Town Fool” in costumes and parades before heading off to San Francisco in 1973. There, Anna Banana met Bay Area Dadaists, Mancusi, Gaglione and Chickadel, and she married Gaglione, collaborating with him in numerous performances including a Futurist Sound Tour of Europe in the fall of 1978. Banana’s own 1971 publication, The Banana Rag, was a magazine about anything related to bananas, and it helped introduce the Bay Area Dadaists to mail art in 1974. Banana’s editing experiences led to important artistamp publications in the late 1980s and throughout the 1990s; International Art Post (1988), Artistamp News (1991-1996), and the Artistamps Collector’s Album (1990).

“He had a Dada tattoo” was the last line of the 1998 New York Times obituary for James Trenholm. 15 Better known as Buster Cleveland (1945-1998), a 1981 interview by the late LA mail artist Lon Spiegelman relates Cleveland’s knowledge of Zurich, Paris, and Berlin Dadaists. 16 Cleveland was a peripatetic coast to coast traveler through much of the 1980s and is remembered for his N.Y.C. stamp escapades with fellow stamp artist Ed Higgins, and with famed art dealer Gracie Mansion. Cleveland’s colorful “OK Post” stampsheets included collaged found objects, pop art subjects including the Lucky Strike icon; also a recurring icon of his friend, Ray Johnson. Together with E.F. Higgins, Cleveland performed on the streets of SoHo covered entirely with Cavellini artistamps, as Higgins and Cleveland tried hawking stamps to strangers passing by. In 1984, Cleveland and Higgins co-curated “Artists Postage Stamps” at the 13th Hour Gallery in New York City. The playful street performances by Cleveland and Higgins harken back to Cleveland’s M.A.D. days in Mendocino, California.

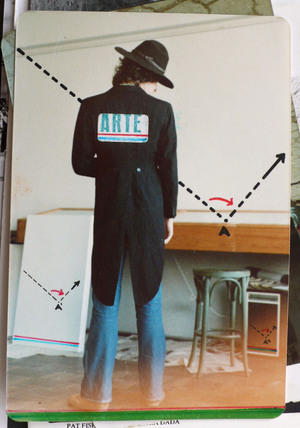

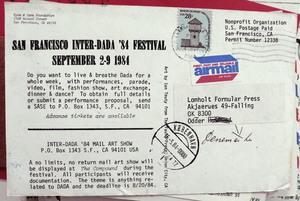

Inter DADA 84

Inter DADA 84 (Sept. 3-9, 1984), organized by Terrance McMahon and Ginny Lloyd was the largest public gathering of mail artists held in the US. It was a week of manifestos, sound poetry at LaMamelle, performances, a fashion show, an open mike, a dinner, videos, photo show, mail art show, Dada Classic Films at the Roxie, and a Dada Around the Block parade. Walter Alter, a self proclaimed artist, heretic, savant, attended the event and recalled, “It (Inter DADA 84) was a hot, sweaty, writhing Karo syrup wrestling pit of aesthetics, a Yucutan Spring Break of the collective Schwittergeist, a juggernaut of mirth and mania.” 17 Telecommunication by fax made it’s debut at Inter DADA as a pioneering interconnection between mail artists attending the festival and participants from Africa, Asia, Australia, Europe, and the Americas. Canadian Net-Art pioneer Lisa Sellyeh and artistampist Michael Bidner connected Canada’s pARTiciFAX Network, organized by the Grimsby Public Art Gallery, through Intelpost telecommunication machines located in numerous public spaces.

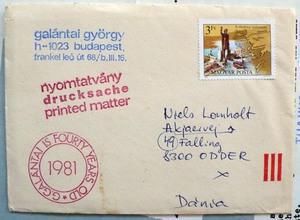

The distribution of North American contact lists and exposure to mail art publications had become a face to face touring phenomenon. Two Neo Dada ladies, Ginny Lloyd and Anna Banana were especially influential as they lectured, performed, and shared their mail art with European and East European mail artists. Lloyd toured Europe twice in 1981 and 1982. In 1981 she met with mail artist Ulises Carrión and Aart van Barnevald in Amsterdam; Rod Summers and Tom Winter in Maastricht, The Netherlands; Ruth and Robert Rehfeldt in Berlin, and Angelica Schmidt in Stuttgart; Michael Giroud in Paris; Vittore Baroni, Emilio Morandi, and Cavellini in Italy; Pawel Petasz in Poland, and Johan van Geluwe and Guy Schraenen in Belgium. While visiting Artpool in Budapest, Hungary, she was invited by Gyorgy Gálantai to collaborate on artistamp issues. After the tour, she wrote Ginny Lloyd: The Mail Art Community in Europe: A Firsthand View. In the preceding decade Anna Banana, also toured and performed in Europe during the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s meeting many of the same artists. The activities of both Banana and Lloyd were certain to have made impressions upon European mail artists, particularly in regard to copier art, artists’ stamps, and zines.

Bay Area Dada member, photographer, and multimedia artist Ginny Lloyd visited Artpool in Budapest and collaborated in the creation of stampsheets with mail artist and director of Artpool, György Galántai. She also connected with Polish mail artist Pawel Petasz and with other East European mail artists. Both her Blitzkunst and Tour ’81 Sketchbook books include many mail artists she met in Europe while lecturing and performing. In the 1970s Lloyd was an active copier artist and in 1980 she organized the Copy Art Exhibition at LaMamelle in San Francisco where she met more mail artists. The show traveled to San Jose, Japan, Germany, and The Netherlands.

Spawning the International Network: Canada’s General Idea, FILE Magazine, Omaha Flow Systems, Image Bank

Several significant developments in North America and Europe occurred within a brief window of time (1970-1974), events that would launch correspondence art into an international network beyond Ray Johnson’s central role as a “correspondence school”. What evolved became an accumulative trend in which, zines, mailing lists and artist curated public exhibitions became the breeding ground for an explosive international, artists’ network. The emerging network aesthetic was a DECENTRALIZED mail art phenomenon embracing many new artforms of social/cultural activism and it revolutionized network distribution on a local and global scale.

Ken Friedman, the youngest member of Fluxus, started creating flux lists as early as 1966. Beyond his role as editor of The New York Correspondence School Weekly Breeder from 1970-1972, Friedman also published the International Contact List of the Arts, a list that at times included as many as 5000 names and addresses. Lists were also accumulated and distributed from German Dadaist Klaus Groh’s International Artists Cooperation. Groh’s IAC No 9 announced Friedman’s Omaha Flow Systems project on page 4. Friedman’s Omaha Flow Systems (Joslyn Art Museum, 1973), is especially important for encouraging the public to select mail art from the Joslyn Art Museum exhibition walls and replace that art with a work of their own. Omaha Flow Systems extended into the Omaha metropolitan region linking an enormous public audience with networking “nodes” at shopping malls, colleges, museums, and public schools. 18 The historic exhibition catapulted mail art into an intricate public communications matrix that reached far beyond anything Ray Johnson had ever intended. In a 1991 correspondence, Ken Friedman remarked, “Ray got a bit cranky when the network started to become a network. As long as it was a few people meeting each and corresponding, it was still Ray Johnson’s New York Correspondance School. Afterward, it was a network.” 19

Meanwhile, in Canada, Vancouver artists Michael Morris, Vincent Trasov and Gary Lee Nova, created Image Bank in 1970; an early databank list that combined Ray Johnson’s N.Y.C.S. with the addresses of international concrete poets who were exhibited in Concrete Poetry curated by Alvin Balkind at Fine Arts Gallery, University of British Columbia. Morris invited Ray Johnson to attend this show in which nineteen of Johnson’s collages were included. Johnson accepted Morris’ invitation and attended the show in Vancouver, one of only two trips in which Johnson chose to travel outside of the United States. 20 Trasov, in “An Early History of Image Bank” mentioned the Image Bank contribution by teacher, copier artist and pioneering networker Dana Atchley, a.k.a. Ace Space Company: “Morris and Trasov contribute to Dana Atchley’s accumulative project Notebook, a compilation of 250 correspondence items redistributed to artists on the mail-art network.” 21 Atchley’s Notebook was an early assemblage project (1969-71) that began a “network consciousness”. 22 “Both Morris and Trasov recognized the value of Notebook and proceeded to include the names of Atchley’s contributors to their Image Bank mailing list.

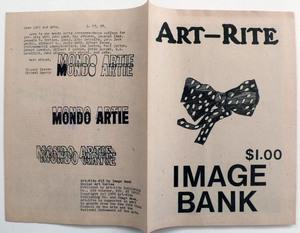

The term “Image Bank”, according to Trasov, “was used by William S. Burroughs in his novel “Nova Express.” 23 Image Bank functioned as an activity in which prints and images of commercial origin were gathered and issued by mail as Image Request Lists. The Image Bank recirculated hundreds of collector artists’ names and addresses with the motifs each collector was interested in. Morris, Trasov, and Nova offered their Image Bank lists regularly to the publishers of FILE Magazine, first published in Toronto (1971) by Neo Dadaists and performance artists collectively known as General Idea (Jorge Zontal, Michael Timms, Ron Gabe, Mimi Page, and Granada Gazella). Patterned after LIFE Magazine, the editors of FILE also used the Image Bank Image Request List to bolster their subscription base.

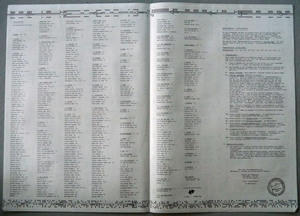

The Annual Artists’ Directory by Image Bank was published in FILE magazine’s February 1974 and it filled the entire issue of thirty-eight pages with 1,200 artist names and addresses. Also appearing were over 450 image requests including Ray Johnson’s listing, “Request images of John Derek,” 24 and Canadian artistamp pioneer, Michael Bidner’s call for “Women in bondage - Asexual or otherwise...Men of any age, esp. the older, wrapped in white foam or cream...plus any subsistence of your head that can float in paper behind a postage stamp.” 25 The hilarious listings appeared in other issues of FILE and in one Christmas issue the lists were meant to facilitate shopping for art addicts. 26 Distribution of FILE included major news stands across America and while short-lived, FILE boasted a large subscription base. Canadian mail artist and artistamp creator, Don Mabie, a.k.a. Chuck Stake, was also a prolific list maker whose publication, Images and Information served as a magazine, newsletter, and mailing list. He also organized with Canadian performance artist, Wendy Toogood, many of Canada’s earliest public mail art exhibitions. Mabie operated some of Canada’s first alternative artists spaces like Clouds ‘n’ Water and Off Centre Centre in Calgary.

Before the internet, the early 1970s non-electronic mailing lists functioned like “slogs”, slow motion snail-mail versions of current online blogs. The accumulative decentralizing effect of these early “networking lists” were larger than any one project or artist and quickly launched the mail art network into an international phenomenon. Fifteen years later, mail artist CrackerJack Kid, a participant in Friedman’s Omaha Flow Systems, took mail art online with The World Wide Web’s first virtual art museum, The Electronic Museum of Mail Art (EMMA). On New Year’s Day, 1995 he organized a cyberstamp mail art exhibition and placed his ezine Netshaker Online on the newly launched World Wide Web’s EMMA site. Remembering the importance of Fluxus lists, Kid applied that concept in establishing The Emailart Directory on EMMA. 27 The Emailart Directory was posted from the spring of 1991-1997 on internet newsgroups including The WELL through the facilities of Dartmouth College’s Kiewit Computation Center.

Europe Goes Global

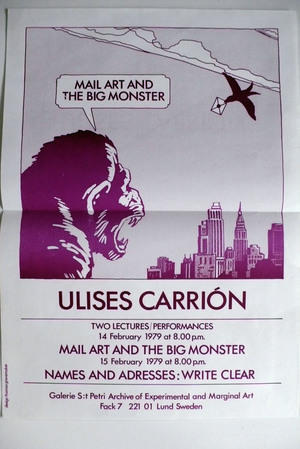

Among Europe’s most influential book artists, visual poets, and mail art theoreticians we find Dutch artist Ulises Carríon (1941-1989), playing a major role in 1979 as one of several first generation mail artists who introduced Europe to artists’ publications. Together, with the late Aart van Barneveld, both established Other Books and So, an Amsterdam gallery devoted to experimental artists‘ publications, video performances, and visual poetry. At Other Books and So. Ulises Carríon viewed mail art in the context of a cultural, international phenomenon and focused on exhibiting rubberstamps and publishing a Dutch monthly bulletin entitled Rubber. Other influential mail art literature by Carríon include his magazine “Ephemera” (1977-78), and his essays “Mail Art and the Big Monster” (1977), and “Rubber Art Theory and Praxis” (1978).

György Galántai and Júlia Klaniczay, Artpool’s founders have archived the thousands of postmodern international artists. Much of Artpool’s collection was acquired during The International World Art Post exhibition and catalogue organized by Artpool from April 6-25,1982 at the Fészek Galéria in Budapest. The exhibition was the largest European assemblage of artists’ stamps ever exhibited at that date. The exhibition catalogue included 27 artist anthology sheets of imperforate stamps, the largest collection of artistamps producers to appear in one document. Over 700 artists from 34 countries participated in the exhibition. Some early examples of Soviet mail art appeared. Among the Eastern Block countries, mail art came from Hungary, East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria, Poland and Romania. An artist from Saudi Arabia sent work from the Middle East and from the Far East, Japanese artists participated. Latin American mail artists were well represented and hailed from Argentina, Brazil and Mexico. Surprisingly, there was no accompanying list of the artist’s addresses.

According to curators György and Julia Galántai, the idea for their exhibition resulted from Giovanni Achille Cavellini’s successful exhibition in Budapest on the premises of the Young Artists Club (May 29, 1980), “which attracted and provoked many Hungarian artists to participation. We thought then of organizing a large scale international exhibition, i.e. as far as that was possible under our present circumstances. We wanted the whole world to appear in one definite place at one definite time.” 28

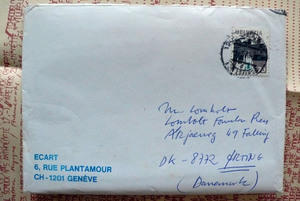

Another important European exhibition of artists’ stamps appeared six years prior to Artpool’s “World Art Post”. John M. Armleder, a painter, conceptual artist, and performance artist from Switzerland, exhibited Timbre et Tampons d’Artists in May 1976, at Cabinet des Estampes, Genève. Armleder founded the group Ecart and ECART Publications, an independent publishing house that introduced mail art and artists’ stamps to European artists.

Mail Art Publications Breaching the Iron Curtain in Eastern Europe

A military, political and ideological barrier known as the Iron Curtain was formed between Soviet bloc countries and western Europe between 1945 to 1990. For nearly three decades the curtain and it’s more concrete cousin, the infamous Berlin Wall, were Cold War efforts to repress and curtail the exchanges of communication and ideas. Mail art interchange by artists within East Block countries and Russia struggled to form creative netlinks to the West. Laszlo Beke, the co-editor of Mail Art: East Europe in International Network, noted that “the striking quality of Eastern European mail art is due to the fact that this art was produced under direct confrontation with dictatorship.” 29

Communist Ideology in Eastern Block countries precluded any possibility of a free market art system. Obviously, art object/commodity issues of Western “free world” nations were irrelevant. Polish mail artist Pawel Petasz wrote, “What differentiated (Polish) mail art exchanges from Western mail art was twofold: first, Polish mail art exchanges were primarily in-country, and second, the major purpose of these exchanges was to create art that challenged or circumvented the restrictive ideology and regulations of the Polish people’s art scene”. 30 The communist regime rigorously restricted all duplicating and printing service from private or public usage. Polish artists exhibited in alternative, semi-independent “student galleries and local cultural centers” 31 that were located in both small and large Polish cities during the 60s and 70s. Government censors prohibited the publishing of books in the local centers, but tolerated show catalogues and printed matter in editions no larger than 100 copies. As such, mail artists gravitated towards those centers.

In Poland, where artists were under conditions of constant surveillance, a remarkable event occurred which defined net activities predating today’s Net.art by nearly forty-five years. Andrzej Kostolowski, a Polish critic and alternative gallery director teamed up with another Polish artist, conceptualist Jaroslaw Koziowski. Together, they published a set of nine network statements they titled “NET.” On May 22, 1972, NET was re-published in Poznan, the former capital of Poland. By coincidence, 1971 was also the same year that French art critic Jean-Marc Poinsot christened “mail art” at the Paris Biennale”. 32 The signers of NET were unaware of Poinset’s “mail art” neologism, but in their gathering began drafting another set of criteria that would eventually become the communication aesthetics that birthed the foundation of mail art networking. The 1972 publication of NET included a list of 26 conceptualists and artists who are known today as first generation mail artists, Julien Blaine, Klaus Groh, Bernd Löbach, and Geza Perneczky among others.

NET remains a significant, definitive mail art document that miraculously arose amidst an oppressive, central communist regime. Summarized, the nine networking points of NET visualized and defined a new era. NET designated an open and uncommercial aesthetic with net origins in private homes, studios, or any other place where art propositions were articulated. The NET had no central point or coordination. Over a decade later, Roy Ascott, the pioneering British telematic artist and theoretician, would write enthusiastically about telematic technology “to carry forward an aesthetic of participation and interconnectedness.” 33 Describing this activity, Ascott declared, “I prefer to use the term “networking” for the activity.” 34 Roy Ascott professed with enthusiasm the hope that “networking” would “amount to a quantum leap in human consciousness.” 35 and proposed “to cite a variety of writers from a variety of disciplines who collectively contribute to a vision of the future of the human condition which is rather hopeful.” 36 Ascott never included mail art in the discussion. The networking world of mail art in Cold War Poland had already set the analog networking precedent to Ascott’s telematic utopia. Mail art was the proto-internet, the analog network, the internet’s skivvies. Mail artists theorized before the advent of the internet, world-wide-web, or the Networker Telenetlink years (1990-1995) that the NET could be anywhere.

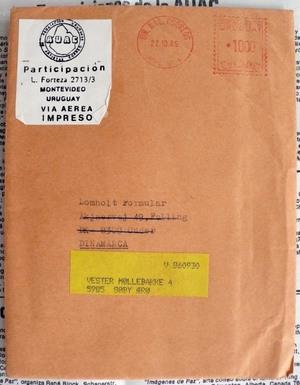

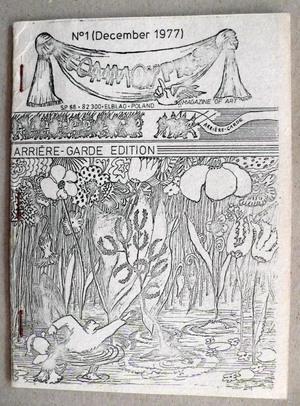

Postal intelligence agents were no strangers to Pawel Petasz and it is certain they knew of his assemblage zine known as Commonpress. Mail artists living in countries behind the Iron Curtain sent catalogs, project documentation and zines that contained cryptic numerology, symbols, and other oblique references to visual subject matter that tested and ridiculed state postal authorities. Mail art embodied the quest for freedom of expression. Petasz wrote about his discovery of mail art in 1975, “It was very exciting to suddenly have a chance to participate in a world in which the Iron Curtain didn’t exist.” 37 In spite of this exuberance, Petasz’ artistic freedom, as many other East European mail artists will attest, was limited by physical and financial circumstances.

Commonpress 1977-1990

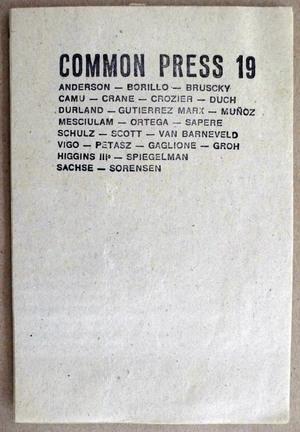

Commonpress was an “assemblage magazine” that emerged as the most prominent publishing series in the history of mail art. For a decade Commonpress was a collaborative, shared editorship with Pawel Petasz as it’s founder and coordinator. Petasz defined it as a “periodical edited by common effort.” The concept of Commonpress involved assigning issues with co-editors picking a theme of their own choosing. Géza Pernecszky, editor of the The Magazine Network, likened the shared editorship of Commonpress to passing a baton. Commonpress editors were invited by Petasz. If a request was made by others desiring to co-edit, Petasz made the final decision to approve future editions.

Not all issues of Commonpress were published by their editors. With no deadlines guiding the project, some editors delayed publication for many reasons. The size of each Commonpress edition was established at 200 copies with a small portion going to Pawel Petasz. The cost of preparation often depended on an editor’s financial circumstances. The highest assigned Commonpress Number was set at 100, but just half were ever published between 1977-1980. Some editors, like Lon Spiegelman passed away. Other life circumstances intervened as well. Brazilian mail artist, L. F. Duch’s Commonpress No. 10, “Post Office” was presumed to have been confiscated by postal authorities. By 1990 most of the published Commonpress editions were finished and the 1980s saw a golden decade of mail art activity seldom matched by mail art zines in subsequent years. Pawel Petasz kicked off the project with a 43 page issue titled “Arriére Garde.” Over a dozen assigned editions were to have been published between 1977 and 1980 but never went to press. The final edition, No. 100 was issued in 1990, but the number assigned to that issue does not reflect or account for the large gaps of missing issues, particularly between Nos. 64 and 93. Nearly two dozen assigned issues were never published. Among the missing assigned issues, two belonged to mail artists who are now deceased; Lon Spiegelman’s “Alphabets,” (No. 21) and Bern Porter’s “Light” (No. 30). A few issues, such as Tanja Erlij’s Commonpress No. 44, a large, remarkable poster issue about “Artists’ Body of Statement/or Secrets” was produced in an edition of several dozen copies. Altogether, complete editions of existing copies of Commonpress are exceedingly rare.

Among the handful of mail artists who succeeded in collecting all or most of the Commonpress issues are several mail artists who have published books about mail art; Belgian mail artist Guy Bleus, Hungarian visual poet, Geza Perneczky and US artistampist/mail artist, Chuck Welch. Each of these artists were also contributors to the Commonpress series. Regrettably, few issues of Commonpress included any notes by the editors describing their choice of theme or their personal biography.

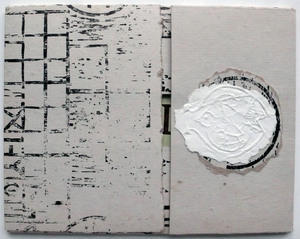

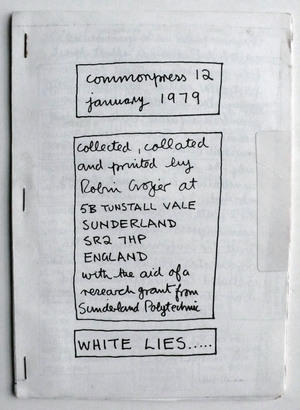

Robin Crozier, Commonpress No 12: White Lies

Robin Crozier was interested in surrealism as a young student in the fifties. In the sixties he found publications about John Cage, Daniel Spoerri, Robert Filliou, and Dick Higgins whose books introduced him to intermedia. By the end of the sixties he developed a life-long interest in concrete and visual poetry. In 1970 he began producing his own magazine, Pages which focused on the avante garde, particularly artists he became acquainted with through Dick Higgins’ Fluxus publication, Great Bear Pamphlet series. Crozier explored the interaction between the intimacy of correspondence art and the heavy hand of mass media communications. Crozier’s projects make associations with original work and how reproductions blurr the sacredness of the original artist’s marks that are normally intended as singular messages of import. In Robin Crozier’s Commonpress issue one can enjoy the contributor’s unpredictable responses to Crozier’s thematic subject “white lies”. When Canadian “femail artist” Anna Banana responded to Crozier’s theme,” she wrote, “My white lies don’t show up on white paper.” Another respondent answered that white lies might suffer a “white-out” in the printing...a nod to correction fluid commonly used in the age of electric typewriters.

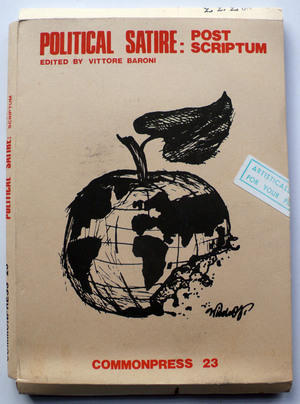

Vittore Baroni, Arte Postale! and Commonpress No 23: Political Satire: Post Scriptum

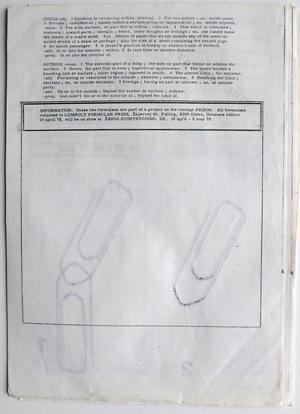

A few Commonpress issues such as Baroni’s issue No. 23 and CrackerJack Kid’s “Material Metamorphosis” issue No. 47 doubled as international mail art exhibitions in public spaces. Baroni’s show was exhibited at the Forte dei Marmi Municipal Library from September 1-16, 1979. Baroni was one of a few artists to receive funding to produce his issue of Commonpress. Help came from a committee of the 7th annual “Political Satire/Forte dei Marmi Festival. Commonpress No. 23 was hand-assembled (110 pages) in an edition of 500 copies, one of Commonpress’ largest editions.

The story of Arte Postale! has been written by it’s editor, Vittore Baroni and appears on the internet. 38 He is accurate in claiming that Arte Postale! is “one of the most well known and long-lived magazines” in the mail art network. Baroni, an art and music critic, is a prolific creator of numerous zines, comics and authoritative books about underground art forms. According to Baroni, the publication was continuously issued over a period of sixteen years. During that time, over 500 mail artists participated from 35 countries. Ray Johnson, father of mail art, participated as did Fluxus artist Ben Vautier. Copies were free to all participants. Baroni, upon recalling the creation of Arte Postale!, said, “When I started utilizing the mail art net, I was looking for something that the traditional art system could not give me. At that time, in the late seventies, I tried to restrain myself as much as I could from creating ‘fine’ images. I did not want to make ‘artworks’ and develop a style to please myself aesthetically. I wanted to find new ways to communicate my ideas, avoiding all the usual traps and clichés of the gallery-museum-critic-art magazine routine.”

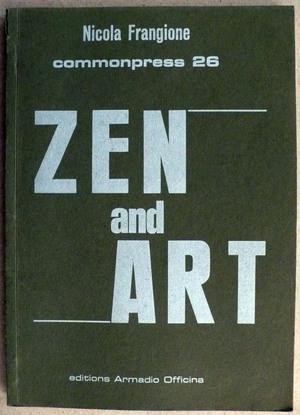

Nicola Frangione, Commonpress No 26: Zen and Art

Frangione’s edition was based on the theme of “Zen and Art.” Over 85 responses were recorded on 89 pages. Many of the participants were contributors to previous issues of Commonpress and included notable artwork by Latin American network participants like Edgardo Vigo, A de Araujo, Paulo Brucky, L. F. Duch, Falves Silva, and Aaron Flores. Italian mail artists V. Baroni and Cavellini sent contributions. Also appearing was German mail artist, Robert Rehfeldt (1931-2007), who was responsible for building up an extensive network of contacts between East and West Europe, the US and Latin America. Miroljub Todorovic, a prominent Serbian visual poet and theoretician of Signalism, offered a set of four artists’ stamps about mail art and signalism. Commonpress No. 26 is paper bound and published in an edition of 300 copies.

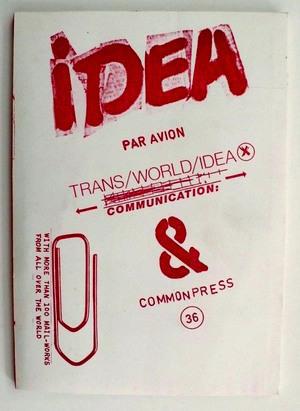

Günther Ruch, Commonpress No 36: Idea and Communication

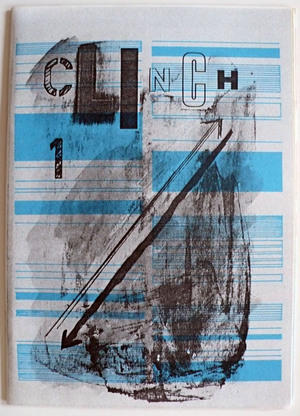

Gunther Rüch (1942-2013) was a Swiss mail artist and editor of the network-assembling magazine, Clinch (1983-1988). Together with Hans Ruedi Fricker, Rüch was the co-creator of the 1986 Decentralized World Wide Mail Art Congresses. In 1980, he created a superb, perfect bound issue of Commonpress that reflects his intellectual curiosity and skill as a graphic designer. The subject for Commonpress No. 36 centered on the “idea of communication” and Rüch summarizes the concept succinctly in his concluding remarks, “Understanding has not only to do with language. There is no good or bad communication, there is communication or no communication.” The first chapter of this text was written by Dr. Klaus Groh, a German dadaist, who observed, “Many examples of these (mail art) artistic activities can be found in the CSR, in Hungary, in Poland, in the GDR, in Bulgaria, in USSR, in Yugoslavia and Romania. These artists work together, organize meetings in small public circles and they even publish their ideas in letters and postcards.” Commonpress No 36 was perfect bound, 92 pages, and published in an edition of 200.

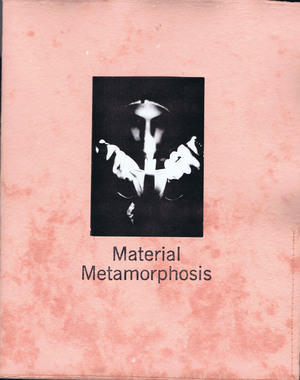

CrackerJack Kid, Commonpress No 47: Material Metamorphosis

The CrackerJack Kid created Commonpress No. 47 by choosing a theme that would link his hand papermaking activities with mail art networking. Craig Saper, in Networked Art called the project, “The most successful intimate bureaucracy involving craft as conceptual art.” 39 130 artists from sixteen countries participated. The Kid received “favorite articles of clothing” that he pulverized into cotton pulp metamorphosed into handmade paper stationery. Each artist received their “clothing stationery” and were asked to return one envelope and letter to be used as a way to reveal “self-identity.” Ray Johnson, the father of mail art, sent the Kid webbed underwear. Said Johnson, “The webbed material I sent you is part of underwear. I cut with scissors the front and back of the underwear. The webbed material is two sides of the underwear. I wore that underwear for years and the older it got, the more droopy it became. It stretched and stretched, and has or had no sentimental value. The day you telephoned that underwear was in the kitchen garbage bag at the bottom of the bag”. Commonpress No 47 included 67 looseleaf pages placed in sewn sleeves. The folio was created in 1982 with handmade paper formed at Sandbar Willow Mill, the Kid’s South Omaha basement studio.

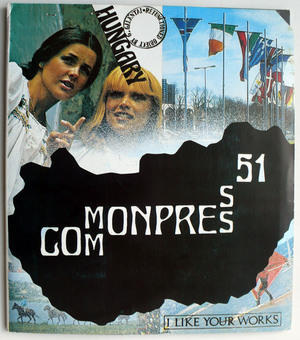

György Galántai and Júlia Klaniczay, Commonpress No 51: Hungary

The “Hungary” edition of Commonpress 51 was created in 1984 in an edition of 320 copies. Co-editors, Júlia Klaniczay and György Galántai are also the directors of Artpool, a non-profit archive that doubles as an exhibition and performance space in Budapest, Hungary. Since its inception in 1979, Artpool has been the center of East European avante garde art. During the 80s Artpool was a leading gateway connecting the western “free-world” with East European artists. Commonpress No. 51, like several other issues of Commonpress, was created to double as an exhibition catalogue and mail art publication. Subsequently, Commonpress No. 51 was linked thematically to the “Hungary Can Be Yours/International Hungary” exhibition that originally opened on January 27, 1984 at the Young Artists’ Club in Budapest. The show was immediately banned by the secret police who filed a report claiming it as a mocking “attack (on) our state and social order as well as the state security organs. “ At the closing of the show, only 25 copies of the Commonpress 51 “Hungary” issue were produced. Later, following the political upheavals in 1989, an exact reconstruction of the show was held. At that time the remaining copies of Commonpress No. 51 were issued in 300 copies. This issue was color offset whereas the first 25 copies were produced by photocopy. According to the Artpool website, “The topic ‘Hungary’ was inspired by the imaginative ‘Italian boots’ of the Italian poet Adriano Spatola’s ‘Italy issue” (Commonpress No. 9).

Guy Bleus, Commonpress No 56: Exploring Mail-Art

The Belgian mail artist and theorist Guy Bleus conducted brilliant, thorough studies of all variations of contemporary communication such as his Telegraphy and Mail Art Project (1983). A year later Bleus edited Commonpress No. 56, a comprehensive project organized in four parts; “the text ‘Exploring Mail-Art, the aerogramme project ‘B.T.S.’, the Commonpress-retrospective (1977-1984) and an appendix. It contained 4 microfiches. In all, more than 800 pages (Dn A4) are photographed on microfilm: reduction 1/42.” Further on in the publication (p. 113), Pawel Petasz listed 13 objectives of Commonpress pointing out a desire to make room in the editions for more text....”to be encouraged, to get more than a simple anthology.” Petasz was fine with editors who wanted to include mail art projects in Commonpress, but he wanted future issues to contain more content than merely a catalogue of pictures for participants. He advised, “We have to be ambitious.” Guy Bleus’ Commonpress No. 56 is one of the most ambitious editions, if not the most exemplary Commonpress project that presents texts that explored mail art’s psychology, history, practice, sociology, art criticism, ethics, communication, phases of receiving and decoding, and many other subjects.

Latin American Contributions to Mail Art Printed Matter

The face of mail art can be subversive, agitative, combative and anti-authoritarian. Anger and hostility were felt not only by mail artists in East Europe, but also in Latin America where zine creators were persecuted with censorship, incarceration, disappearances and exile. In the Latin American countries of Brazil, Uruguay, Chile, Argentina, Columbia, Venezuela and El Salvador mail art was a politicized art that not only challenged aesthetics, but also attitudes toward the role of art. Zines magnified that viewpoint.

Conceptual forms were often the content of Latin American artists’ publications. Forms embraced language and ideas as an “aesthetic more concerned with reality than with abstraction.” 40 In the mid 1960s, Latin American artists departed from a world of crafts and disciplines and embarked upon a world of utopian ideas informed by European Arte Povera, Situationism, North American conceptualism, and concrete poetry which was officially launched as a movement during the National Exposition of Concrete Art at the Museum of Modern Art, Sao Paulo. 41 The formalism of concrete poetry, however, represented concepts rather than things in the world. Visual poetry, generally less text dependent than concrete poetry, blurred differences between visual and textual forms so that images crossed into texts and texts crossed into images. Ultimately, Latin American mail art publications emerged as a utopia awakened.

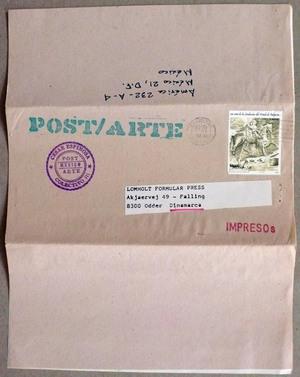

Cesar Espinosa is a leading Mexican visual poet, theorist, and producer of numerous rubber stamp and mail art publications that convey a theme of political activism, especially the liberty of Latin America and the Caribbean. In 1981, Espinosa was one of the founding members of the Colectivo-3 Group which developed a collective poem titled “Revolution”. Comprised of 350 artists from 50 countries, the group summarily rejected the art market by stating, “The information and the process are in the centre of the creative act, not the ‘opus’ for sale and speculative prestige.” Espinosa also edited Postextual in 1986, a visual poetry and mail art zine which found its way into the street art of Mexico City and through international circulation via the mail art network. Espinosa is credited for creating a Chart of “Mail Art in Mexico”, a rare document that’s important for tracing the involvement of a dozen Mexican mail artists and their projects/publications dating from 1976-1984.

The mail art and publications of Cesar Espinosa resonate with political and social criticism. 42 He remains one of the founders of the political organization known as The Latinoamerican and Caribbean Mailartists Association. He is a constant, tireless spokesperson for hope, equality, and justice. In contemporary art. Espinosa sees the continuation of mail art issues carried out over the internet and email mostly by young students of different disciplines of communication. Not surprisingly, since the advent of Mexican mail art in 1972, Espinosa has observed a constant hostility towards visual poetry and mail art among cultural authorities, critics, poets, and professional artists. 43

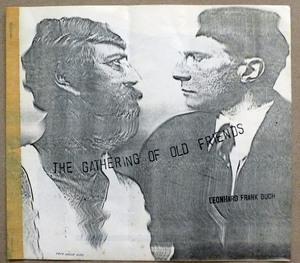

The self published magazines and pamphlets of Clemente Padin, coupled with similar works by Paulo Bruscky, and Leonard Frank Duch are distinguished for their pioneering work which were among the first manifestations of mail art in Latin America. They were also among the first Latin American mail artists with access to black and white copier technology in the creation of mail art publications. 44 Luis Camnitzer, in his book Conceptualism in Latin America, observed that mail art pieces were heavily influenced by the availability of photocopying machines”. 45

Unlike Brazil, Uruguay, or Argentina, the Caribbean island nation of Cuba was quarantined by U.S. Cold War policies and was consequently unable to participate in mail art, or copier art activities. Furthermore, Fine Arts critics and institutions within Cuba had no interest in mail art. It wasn’t until 1995 when Abalardo Mena, curator of Foreign Art at the National Museum of Beaux-Arts, Havana, introduced mail art to Cuba with the exhibition, Habana ’95: Exhibición Internacional de Arte Correo. Mena, in correspondence dated, May 1995, wrote, “In Cuba few people know about mail art and few practice it, Here, (Cuba) the mail costs are maybe lower than the USA’s but you can’t find a stamp machine, or xerox for reproducing drawings/artworks. Such a machine (or a PC) costs $3,000 USD.” 46

Xeroxed copier art and zines flourished in Latin America during the early 1970s. From 1974 until the mid 1980s, Clemente Padin created many small pamphlets and zines in Uruguay. In 1970, Paulo Bruscky’s artwork focused on experimental research in new forms such as happenings, rubber stamps, audio art, super-8 movies and copy art. 47 Paulo Bruscky and L.F. Duch also co-edited a xeroxed issue of Polish mail artist, Pawel Petasz’ magazine assemblage, Commonpress. The cover of Commonpress #10: Post Office included a xeroxed sheet of photo-montaged Brazilian postage stamps created by Bruscky for the edition. 48

Leonard Frank Duch’s tastes were decidedly more eclectic than commercial. Not only was Duch an accomplished copier artist, but he also was a creator of hand carved rubber stamps. Before his interest in mail art, Duch was a painter, filmmaker, and performance artist. He won art prizes at the Annual Art Salons in Brazil in 1984 and 1987 and appeared in the 1981 XVI Bienal in Sao Paulo where he was invited to talk about mail art. One of Duch’s first forays into international mail art was an ambitious effort with Paulo Bruscky to organize the December 1975-January 15, 1976 Primeira Exposicao Internacional de Arte Postal in Recife.

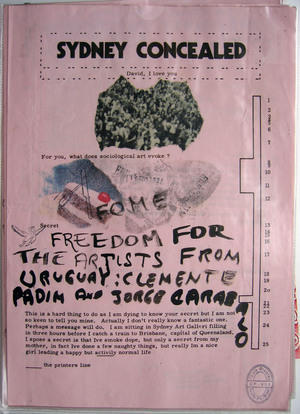

The Risks of Public Resistence: Incarceration, Disappearance & Exile

Incarcerations occurred in Latin America including the jailing of Brazilian visual poets and mail artists Paulo Bruscky and Daniel Santiago. While both artists were attempting to launch the International Exhibition of Mail Art, August 27th, 1976, authorities closed the show just minutes after 3,000 works of mail art were presented in the foyer of the Central Post Office of Recife, Brazil. Bruscky and Santiago were jailed for three days. All of the hundreds of pieces of mail art from twenty-three countries were confiscated and released three months later with many pieces permanently missing. Mail artists Paulo Bruscky (Brazil), Daniel Santiago (Brazil), Leonhard Frank Duch (Brazil), Edgardo Vigo (Argentina), Graciela Gutierrez Marx (Argentina), Jorge Orta (Argentina), Clemente Padin (Uruguay), Guillermo Deisler (Chile), Damaso Ogaz (Venezuela), Jorge Caraballo (Uruguay), Jesus Galdamez Escobar (El Salvador), Cesar Espinosa (Mexico) and others created mail art publications, postcards and copier art that were distributed as symbolic, covert criticisms against repressive regimes. Postcards and zines were chosen as weapons of resistance because these forms were economical and readily available. The Latin American artists who passionately embraced these marginal forms risked incarceration, house arrest, torture and exile.

Attempted assassinations and exile befell Guillermo Deisler. He was a famed editor of the zine UniVERSE and a teacher of graphic design at the University of Chile until Pinochet attained political power after the military coup of September 11, 1973. Many of Deisler’s colleagues were arrested and forced into exile for political beliefs expressed in their visual poetry. In April 1981, the military dictatorship in El Salvador kidnapped the El Salvador visual poet and mail artist, Jesus Galdamez Escobar. Fortunately, Escobar managed to avoid assassination by fleeing his native country and finding asylum in Mexico. Paulo Bruscky commented upon the exile of his friend, “It is always the same; those who pretend to ‘own culture‘ will always try to impose their methods.” 49

Edgardo Vigo, one of Latin America’s first initiators of mail art, published three magazines - WC, Diagonal Zero, and Hexagono. In 1976, Vigo's son, Palomo was a victim of Argentina's military right-wing terrorist state in which thousands of students, journalists, and activists were killed or "disappeared". Vigo's poetic message was always one of "remembrance" for his son, a celebration too in the way mailed messages could escape the boundaries of institutions and bureaucracies. Edgardo Vigo's exquisite work rejoiced in the liberty of free, open communication unhindered by definition.

The influence of Argentine philately and rubberstamps clearly made an impression upon Argentine mail artists, Edgardo Antonio Vigo (1927-1997), and Graciela Gutiérrez Marx in the production of Our International Stamps/Cancelled Seals. Graciela Marx edited Commonpress No 19 in 1979. She is a printmaker, installation artist, and performance artist who learned of mail art through collaborations with Vigo. Eventually, their names were merged as artworks by G. E. Marx-Vigo. Both artists’ works were published in Commonpress No 19 with two dozen other mail artists representing three continents; Europe, North America, and Latin American. The theme, “Pigeon of Freedom,” included remarkable rubberstamps sent by artists including Paulo Bruscky who hand stamped a delivery stork rather than a pigeon. East German artist Karl Sachse sent a dead dove.

The function and purpose of printed matter in Latin America echo Paulo Bruscky’s description of mail art’s role; to bring power back to art and artists through information, protest, and a pursuit of justice. The potency of this message is apparent upon viewing Bruscky’s self-portrait stamp submitted and published for The International World Art Post catalogue organized by Artpool in 1982 at the Fészek Galéria exhibition in Budapest. A stark, bold image of Bruscky’s sombre, bearded face includes the word “POST” inscribed over his forehead. The word “URGENT” looms above the right side of Brusky’s head against a gallows pole with a hangman’s noose leading the eye to a dark, uppercase text identifying “BRAZIL”. Critics who portray mail art as an ineffective dreamer’s utopia need to see this stamp and hear Brusky’s piercing scream.

Such mail art works are powerful global messages. We have seen how mail art publications, zines, exhibition catalogs and project documentation exist with a dual purpose that is both pubic and private while mail artists struggled against art as a commodity fetish in North America. East European mail artists, bereft of supplies, found themselves isolated from the world by repressive political ideologies. In Latin America, the didactics of liberation thrived and multiplied as mail artists bravely defied military juntas. Some were jailed, tortured, exiled and others paid with their lives. The artists represented in this paper are but a cross section of a larger archival living history. 50 Mail art zines, artists’ books, project documents and exhibition catalogs resonated with a communal voice. Mail artist publications and public art continues today; a global epistle resonating with communication.

Notes

1. David Cole, Ein-Hod, Israel,1985.

2. John Held, Jr., Mail Art: An Annotated Bibliography (Metuchen, N.J. & London: Scarecrow Press, 1991). xvii.

3. Stewart Home, “The Assault on Culture,” http://www.stewarthomesociety.org/ass/ma.htm

4. The CrackerJack Kid a.k.a. “Cracker” decided in 1978 to place a surprise in every mailbox. His ghost writer is Chuck Welch, editor of Netshaker, Netshaker Online and webmaster of (EMMA) The Electronic Museum of Mail Art, mail art’s first online website.

5. Donna De Salvo and Catherine Gudis, Ray Johnson: Correspondences, (Columbus, Ohio: Wexner Center for the Arts, 1999), 188.

6. Géza Perneczky, The Magazine Network: The Trends of Alternative Art in the Light of Their Periodicals 1968-1988 (Köln, Germany: Edition Soft Geometry, 1993), 50.

7. R. Pieper, “Ray Johnson (Conversation with R. Pieper),” Mail Art Etc.,” ed., Bonnie Donahue and Ed Koslow, (University of Colorado, Tyler School of Art, and Florida State University, 1984), 16.

8. Ray Johnson and Marcia Tucker co-curated “New York Correspondence School” Exhibition was held at the New York Whiney Museum of American Art, September 17, 1970.

9. Mark Bloch, Franklin Furnace Fracas, http://www.panmodern.com/franklinfurnace.html

10. Janet Jenkins, ed. In the Spirit of Fluxus, (Minneapolis, MN: Walker Art Center, 1993), 20.

11. Ken Friedman, “The Early Days of Mail Art,” Chuck Welch, ed. Eternal Network: A Mail Art Anthology, (Calgary, Alberta, Canada: University of Calgary Press), 1995. 8.

12. JB, “Interview with Monte Cazazza,” Slash (November, 1979): http://undergroundmusiclibrary.blogspot.com/2005/12/interview-with-monte-cazazza-slash1979.html

13. Crane and Stofflet, Correspondence Art, 183.

14. Annmarie Chandler and Norie Neumark, At A Distance, (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005), 477.

15. Holland Cotter, “Buster Cleveland, 55, Dada Artist Known for Collages and Mail Art,” New York Times (May 25,1998): Obituaries.

16. Lon Spiegelman, “1981 Interview with Buster “Dada” Cleveland,” Spiegelman’s Mail Art Rag (November 1984): 6-7.

17. Ginny Lloyd, “Little Known Facts About Inter DADA 84,” http://interdada84.blogspot.com/2010_03_01_archive.html

18. Chuck Welch, Networking Currents: Mail Art Subjects and Issues, (Boston, MA: Sandbar Willow Press, 1986), 29-30.

19. Ken Friedman in a letter to Chuck Welch dated February 15, 1991.

20. Vincent Trasov, “An Early History of Image Bank,” http://vincenttrasov.ca/index.cfm?pg=cv-pressdetail&pressID=3

21. Trasov, Ibid.

22. Crane and Stofflet, Correspondence Art, 237.

23. Trasov, Ibid.

24. General Idea, File, (Toronto, Ontario, Canada: February 1974), 18.

25. General Idea, 19.

26. Géza Perneczky, The Magazine Network, 50.

27. Chuck Welch, “The EMMA Emailart Directory,” http://actlab.us/emma/Links/emailartdirectory.html

28. J.&G. Galántai, World Art Post, http://www.artpool.hu/Artistamp/Galantaie.html

29. Matt Ferranto, “Paradox and Promise: The Options of Mail Art,” http://www.spareroom.org/mailart/mis_4.html

30. Pawel Petasz, “Mailed Art in Poland,” Eternal Network: A Mail Art Anthology, Chuck Welch, ed., (Calgary, Alberta, Canada: University of Calgary Press,1995), p89.

31. Petasz, p89.

32. Ruud Janssen, “Ruud Janssen with Robin Crozier,” TAM Mail-Interview Project (Tilburg, The Netherlands, 1994) p1.

33. Roy Ascott, “Art and Telematics - Towards a Network-Consciousness” in Redaktion, ed. Heidi Grundmann (Vancouver: A Western Front Publication, 1984), p33.

34. Ascott, p33.

35. Ascott, p33.

36. Ascott, p33.

37. Petasz, p89.

38. Vittore Baroni, “Arte Postale! Story,” http://www.reocities.com/paris/5979/postale.htm

39. Saper, p134.

40. Luis Camnitzer, Conceptualism in Latin American Art: Didactics of Liberation, (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2007), 72.

41. Saper, Networked Art, 80.

42. Löbach, Bernd, The Bible of Artists’ Postage Stamps: International Artists’ Postage Stamps Exhibition Weddel, (Cremlingen, Germany: Designbuch Verlag, 1985), 68.

43. César Espinosa, “Mail Art and Visual Poetry in Mexico: Practice (yet) Corrosive, Heterogénesis: Revista de Artes Visuales,” No. 45: Arte Postal, 2.

44. Copy technology had been in place since 1964 when Xerox acquired patent and marketing rights to Central and South America from The Rank Organisation. See: http://www.fujixerox.co.nz/library/f12a2125-fd31-4116-ad7a-7204b78ca41a.cmr

45. Camnitzer, Conceptualism in Latin American Art, 78.

46. Abelardo Mena in correspondence to Chuck Welch, May 6, 1994.

47. Pianowski, “Mail Art: The Net Out of Control,” 213.

48. Géza Perneczky’s The Magazine Network, p. 265, lists Commonpress #17 as having never been edited and that “half of the works were stolen”. A copy appears in the author’s Eternal Network Mail Art Archive, proof that some of the 62 contributing mail artists received the edition.

49. Fabiane Pianowski, “Mail Art: The Net Out of Control,” in Maqueta Padrao, Art and Digital Architecture: Net.Art and the Virtual Universe, (Página: 2008), 210.

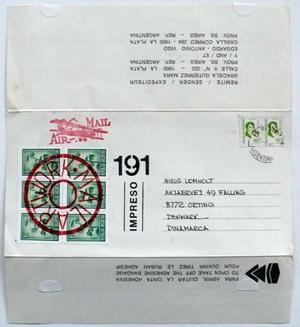

50. This paper is not meant to be a complete account of the multiple forms of mail art publications. The writer acknowledges that significant contributions of important mail artists may have been omitted, but not necessarily forgotten. A detailed account would require a book involving detailed research at several major mail art archives. Artworks in this paper were culled from The Niels Lomholt Archive, a remarkable, varied collection of art. The years 1970-1985, for example, represent the era in which Niels Lomholt interacted with many first generation mail artists...This era was the focus of my research.